A baker and businessman hopes for access to affordable credit.

Rosy is extremely capable; she financed her own migration to Colombia, managed childcare responsibilities for three children, and recovered from multiple threats, robberies, and physical violence against her small family. However, the lack of physical security and her inability to count on anyone else to provide safe childcare while she works is wearing on Rosy, and she can’t imagine staying in this situation for much longer.

Rosy tightened her arms around her son thinking of the memories brought up by our interview. The threats and bouts of violence she faced, especially those targeting her children, left a mark of fear despite her young age. At 30 years old, she has faced outsized responsibility since she was a girl.

Rosy has worked full-time since she was seventeen. Her parents divorced when she was young, so her mother bought a restaurant to support the two of them without her father. Rosy worked at her mother’s restaurant to help contribute to their livelihoods. After twelve years, her mother’s chronic back pain got the best of her, and she was forced to sell the restaurant. Rosy began working as a cashier at a bakery in town and soon became responsible for making sure all the money was accounted for at the end of the night. One day, she caught another employee stealing money from the cash register and reported it to her boss. Her employer soon promoted her to be general manager of three bakeries.

However, Rosy lost her job during the economic downturn in Venezuela that began around 2015. Seemingly from one day to the next, everyone around her started going through the same experiences of scarcity: food shortages, medical shortages, sometimes even shortages of basic utilities like clean water. Around the same time, she gave birth to her son and gained full custody of her niece from her sister. They moved to a new town, and Rosy found a new job at a Subway franchise in a mall. It was a stable job, a short commute from her house, and it allowed her to pay rent. Even more importantly, it provided an avenue through which she could use her social capital to buy food for herself, her mother, and the two children at a time when many Venezuelans were standing in line all day to buy a single kilogram of rice.

After the weekly delivery truck to the store was unloaded, her boss would let all the employees buy leftover supplies in bulk. Sadly, neighbors began to take notice of Rosy’s success in securing food for her family and began to target her. She was robbed twice, leaving the family with nothing but the clothes on their back. Members of a gang attempted to kidnap her son. Rosy knew she had to leave Venezuela to escape their extortion. She decided to go to Colombia.

Rosy had heard terrible stories about the journey to Colombia, and she had no way to care for both children while beginning a new life there. Her brother-in-law sold his car to help pay for the trip, and she sold her hair. Rosy embarked on the trip alone, facing threats from members of the same gang but survived.

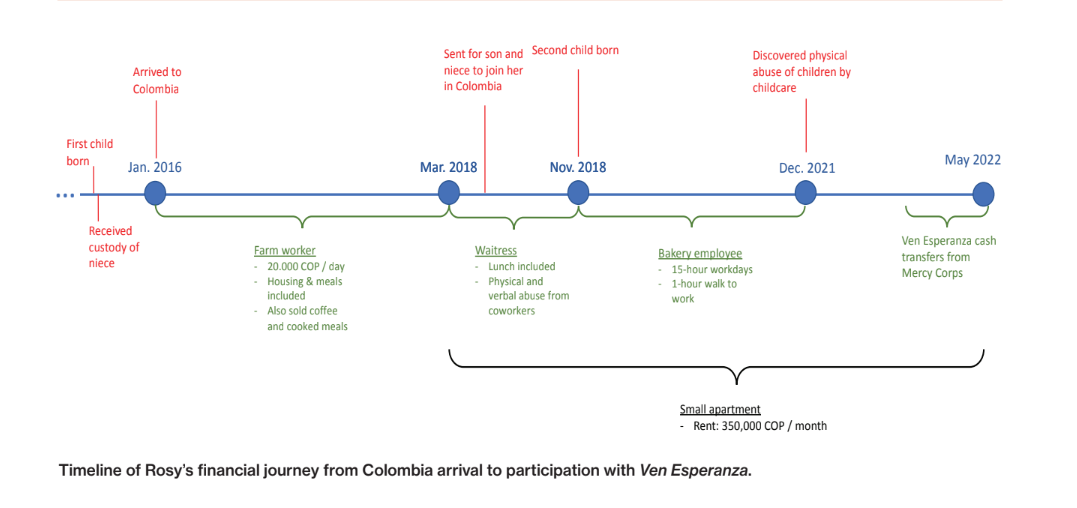

Rosy arrived in Cartagena, Colombia, and found work on a farm where she was given free housing and food. She supplemented her farm income with side hustles like selling coffee and cooking for others. She was making up to $5 USD per day. The free housing and food allowed her to send most of her earnings back to Venezuela for her son, niece, and mother. As the economic situation worsened in Venezuela, she began sending food and diapers in addition to cash, though she still had no savings and few belongings.

After two years in Colombia, Rosy felt secure enough to send for her son and niece. She had stable housing and a regular restaurant job with wages that would cover housing and food costs for her household. Sadly, the job quickly became a nightmare. Other workers at the restaurant began to abuse her verbally and physically, telling her that Venezuelans are lazy, throwing her meals on the floor, or breaking the glasses she was cleaning. Rosy found out that she was pregnant and started to experience vertigo. Eventually, when the other workers at the restaurant began physically assaulting her, she quit the restaurant in search of another job, fighting to keep the growing baby safe.

Without formal work authorization, the only other employment Rosy could find once she had given birth to her daughter was at a bakery. It was an hour’s walk away, and she had to work fifteen-hour days. Isolated from any family member or other social support, Rosy’s main barrier to working was ensuring her children had supervision during her long workdays. Rosy asked a neighbor to watch her three children for $15 USD per week, plus food for Rosy’s children to eat throughout the day.

Rosy grew concerned about this childcare option when she noticed her children were losing weight. She found out that her children were not being fed and were being beaten and left out of the house by the neighbor. Once again, she realized, she would have to leave her job due to violence—this time against her children.

Without further work prospects, compounded by her childcare needs, Rosy is surviving on help from Good Samaritans and cash assistance from Mercy Corps’ Ven Esperanza program, receiving about $88 USD per month for six months. Rosy’s expenses generally exceed her income. Each month, she pays approximately $85 USD in rent, $1.50 USD for water, $8.50 USD for gas, $4 USD in electricity, and monthly food for her family often is $49 USD. Mercy Corps’ cash assistance covers the majority of her rent, and she asks some of her neighbors for food on credit, which she eventually pays back. She does not use credit lines from shop owners or loan sharks, fearing debt cycles.

Currently, Rosy says her biggest obstacle besides childcare is getting her Colombian residency permit (PPT). Rosy has been waiting almost a year for her documentation to arrive. She hopes that once she receives it, she will be able to access higher-paying formal jobs, as well as subsidized day care and medical care for her children. She is trying to save up to migrate to the United States sometime next year.

Rosy has been displaced from jobs and homes by multiple threats to her family’s safety, yet each time she has rebuilt a new livelihood strategy based on the jobs and resources around her. She is searching for a safe place where she and her children won’t be displaced yet again. Though she’s currently out of work, Rosy knows her own strength and trusts that she will continue to find ways to support her children, despite the odds.