Two professors learn to thrive in their new communities.

In their previous lives in Venezuela, Vanessa and Leo held multiple degrees and worked in high-paying jobs as professors. They journeyed to Colombia, where they knew no one and had to ask for help to overcome hunger and unemployment. Though their degrees may not transfer officially in Colombia, the trappings of their higher socioeconomic status - impressive job experience as professors and experience in formal education – alongside Vanessa’s resourcefulness and persistence in reaching out to companies and organizations, made it easier to access opportunities for better paying jobs, even leading to savings and entrepreneurship. Vanessa and Leo have moved beyond survival to fully thriving and giving back to the community they leaned on during their first year in Colombia.

Vanessa and her husband Leo both worked as professors before the economic crisis in Venezuela. Just after having their second child in 2018, the financial situation had worsened to the point that they could no longer work, and they realized they could no longer stay in Venezuela. They knew they needed to relocate their family somewhere they could gain an income and provide food, housing, and schooling for their children.

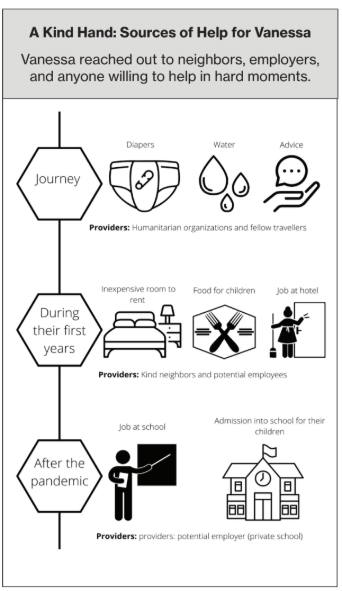

In March 2018, Vanessa and Leo sold everything to pay for their family’s trip to Colombia. During the journey, Vanessa and her family encountered deprivation and hardships unlike any they had ever experienced, lacking basic goods like sufficient water or diapers for the baby. The people and humanitarian organizations who provided water and diapers along the journey made a strong impression on her of others’ willingness to help.

Vanessa and Leo had no relatives or friends to welcome them to Colombia. They did not even know which neighborhood to go to. They stayed three days at the bus terminal in Cartagena where they had ended their journey, seeking information and trying to decide where to go, until another traveler recommended a low-income neighborhood of Cartagena. They went door-to-door, asking to rent a room. A woman noticed that Vanessa and Leo were traveling with two children and took pity, renting an unfurnished room for $1.20 USD per day, or $36.50 USD per month. The family slept on the floor because they had no mattress.

Vanessa and Leo sold coffee, juice, and fried foods (fritos) in the streets, making $7 USD per day. They spent all their money on rent and food for their children. Refusing to compromise on their children’s nutrition, they fed them twice a day, spending $59 USD per month on food. Vanessa would skip meals if necessary or, if they could not feed the children, go door-to-door asking for help from neighbors.

After three months in Colombia, Vanessa tried selling coffee across the city, seeking higher profits in the upscale beach neighborhood of Bocagrande. Seeing the huge resorts and hotels, Vanessa realized that she could search for jobs at the hotels. At the third hotel where she inquired, the manager offered a deal: if she could stay there and train for three days, unpaid, they could give her a job. Though it was difficult to lose three days of pay, she was confident that the risk would pay off. After the training, she was hired on as a full-time receptionist, earning $7 USD per day. After six months, she obtained similar employment for her husband, raising the household income to $15 USD per day. After six months of higher income and the resultant stability, the pandemic hit. They lost their jobs, and school closed for their older child, whom they had enrolled soon after arriving.

After Colombia’s pandemic lockdown ended, Vanessa began to focus her energy on getting her children back in school, which led to her next job. She attempted to enroll her children at various schools*. After being turned away by all public schools, she resorted to offering her services as a cleaner at a private school in exchange for her children’s admission. The superintendent, upon seeing the extensive teaching experience on her resume, offered her a job as a teacher’s assistant. She was paid $195 USD per month, less than the standard rate and below the minimum wage of $244 USD per month in Colombia, because she didn’t have legal documentation.

Vanessa was soon promoted and given a salary increase, raising her income to $244 USD. The steady income allowed the family to buy a computer and start eating more nutritious meals, spending $85 USD per month on food. They began renting in a nicer house for $98 USD per month, with a utilities rate of $8.50 USD per month.

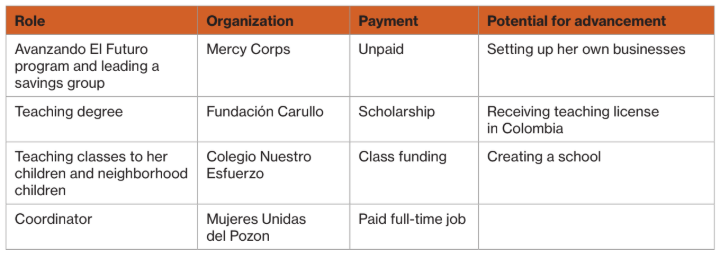

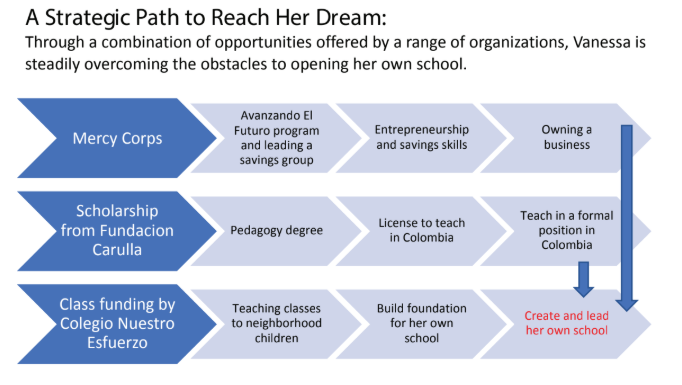

After over a year of work at the school, her unfair pay due to her undocumented status prompted Vanessa to search for other opportunities. She became the coordinator for an organization called Mujeres Unidas del Pozon. She started to participate in Mercy Corps programming and was accepted into Avanzando El Futuro, where she learned about entrepreneurship. She also became the leader of a savings group as part of a Mercy Corps program.

Vanessa received a scholarship from the Fundacion Carullo for her to return to school for a teaching degree, so she could officially teach in Colombia. Now, within her own home, she and Leo also teach their own children alongside other children from their neighborhood. A local education organization, Colegio Nuestro Esfuerzo, is funding these classes at $98 USD per month. The support from these scholarships and programs is leading to further opportunities: Vanessa has plans for a printing business, and she and Leo hope to expand their school for children in their neighborhood.

Vanessa says that 2022 has been her best year. Her intrepidity and determination helped her leverage her and Leo’s educational advantages in Venezuela towards opportunities and entrepreneurship in Colombia. She and Leo have saved up $49 USD over the past two years, which they could invest in one of their business ideas. When she and Leo eventually receive PPT, which they have applied for, they will have wider access to full-time jobs and resources.

*In Colombia, children have to re-register for school every year. When all the spots available in the school are filled, children are turned away. Venezuelan children often face informal discrimination when enrolling.