Written by: Julie Zollmann, Airokhsh Faiz-Qaisary, Kenza Ben Azouz, Kim Wilson,

and Radha Rajkotia

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Refugees resettled in the United States are typically supported quite closely early in their transition as support agencies help them settle into new homes, open bank accounts, get their first jobs, and register their children in school. Agencies monitor whether refugees are “self-sufficient,” meaning that their incomes cover their most essential expenses as quickly as possible. However, little is known about the next stage of refugees’ financial and economic transitions, once refugees are no longer interacting regularly with resettlement agencies.

In July 2018, we interviewed 29 refugees who had been resettled two to three years earlier to understand the phases of their financial transition and identify possible opportunities to accelerate refugees’ financial gains.

Two or three years after resettlement, many refugees have not yet recovered economically to the levels of well-being they experienced before their lives were disrupted, and they ultimately fled. This our respondents attributed to the difficulty of securing professional work and to the high cost of housing and healthcare.

While work is plentiful in the Dallas area, it is often low-paying. Many refugees are trying to acquire professional qualifications—or adapt their qualifications from home—to move into higher-paying careers. But building these skills takes time, requiring that individuals reduce their hours or even leave other jobs for extended periods. That can be difficult to manage, particularly in the face of what feel like high housing costs.

It is tough to save up a few months’ worth of rent when rent itself consumes such a large share of income when refugees are working full-time. As a result, many feel quite precarious. A particular worry is the high cost of health insurance and a fear of unexpected healthcare expenses among the uninsured.

Many of the refugees in our sample arrived in the US with a long history of building assets of their own. They were skilled savers and also experienced in cultivating social networks for borrowing and lending to navigate difficult periods. Those skills transferred to the US, with most respondents very quickly learning to navigate the US financial system and dedicating themselves to saving, often with the ultimate aim of buying a home. However, a year or more after resettlement, knowledge gaps become apparent, often around issues that were not necessarily relevant in early orientation sessions.

Successful economic integration has as much to do with overcoming social fears as with building specific financial skills. Those refugees who were thriving made a point to spend more time in public, to work as a means to be exposed to more English, and to meet new people. In Dallas, being able to work and study is facilitated by conquering another fear for many: driving. Having friends and mentors to tackle new experiences helped many find the courage to get out more and try new things.

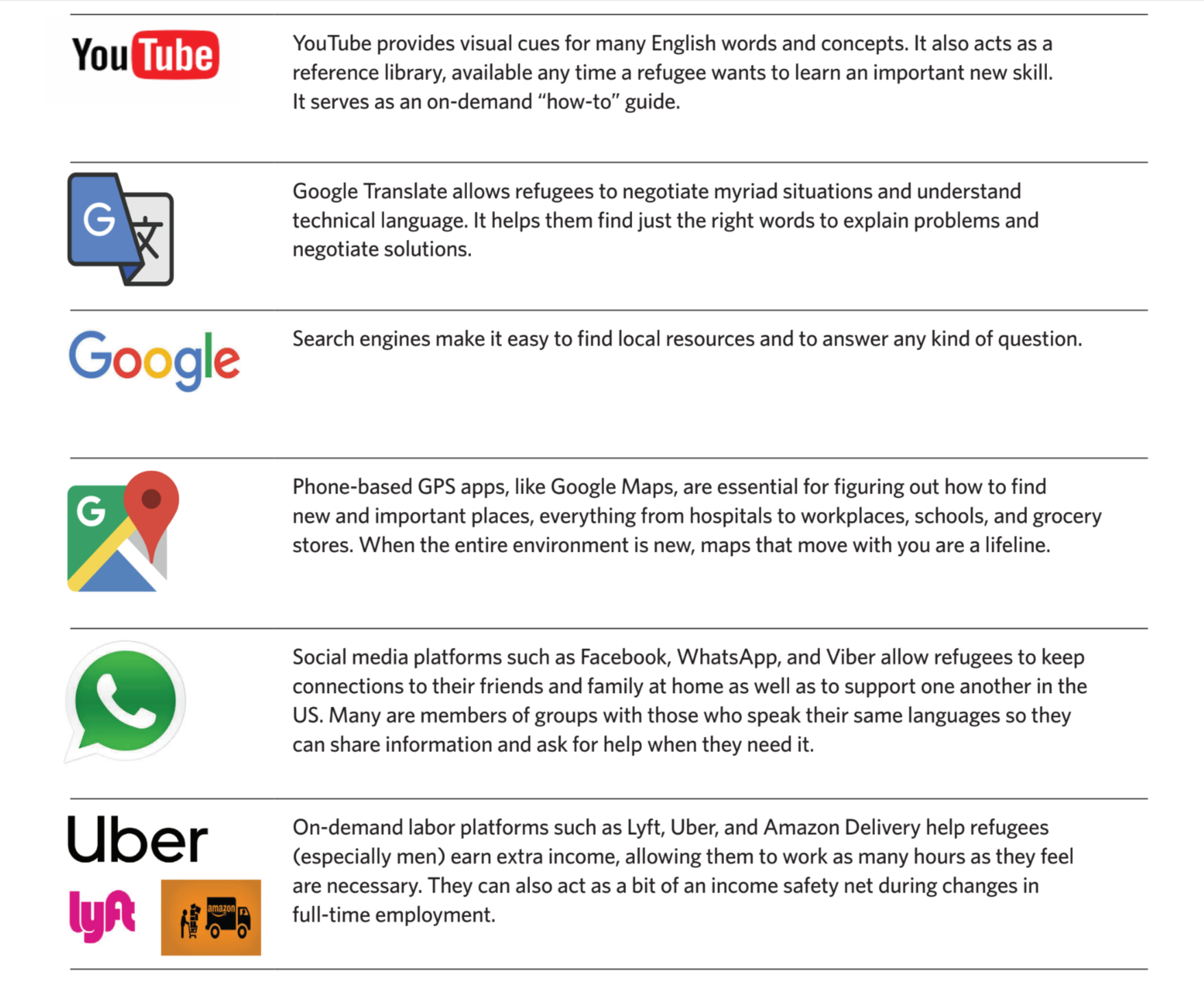

Refugees are already using a wide range of technologies—from WhatsApp to Google Translate—to help ease their transitions to their new homes. Refugee resettlement agencies and community partners can do a better job of leveraging these tools to provide longer-term advice and support to their clients, helping them move beyond mere self-sufficiency and into a place where more of them are thriving in their new home.

Introduction

As debates over migration rage throughout the world, questions often asked are, “How much of a financial burden are refugees and migrants?” and “What is the economic impact of refugees?” A number of studies have shown that immigration is often a net positive for host communities.

A large study in the US found that after eight years, resettled refugees typically pay more in taxes than they receive in state benefits, and after 20 years in the country are significant net contributors.1 Other scholars point out that whether and how these net benefits are reached depends on policy responses, including, for example, under what conditions refugees are able to work legally.2 Are refugees getting the tools they need to thrive financially and economically?

Apart from these large surveys, we do not know in great depth the details of how refugees manage their financial transitions, especially after their immediate arrival in a new country, when they typically are receiving intensive support from humanitarian organizations or—as is the case in the United States—resettlement agencies. Having greater insight into these transitions could help us imagine ways to accelerate refugees’ financial gains, benefiting both refugees and the communities in which they live.

When refugees arrive in the United States, a small set of agencies are contracted by the US government to assist in their resettlement. These agencies have a strict set of deliverables to support individuals and families: securing adequate housing, enrolling them in eligible cash and healthcare assistance programs, and helping them secure a first job. This assistance is most intensive in the 90 days after arrival.

It’s difficult for agencies to know what happens to refugees after this initial period. Might resettlement agencies and host communities be able to do more to better the chances of a resettled refugee’s long-term success? What lessons do those who are navigating the transition well have that might apply to others? What overlooked risks need to be examined more closely?

Research Questions and Approach

This small study was meant to help close this knowledge gap around specific financial strategies and integration mechanisms after the early resettlement period by looking closely at the financial integration of refugees resettled by the IRC in Dallas, Texas, two to three years prior to our interviews in July 2018.

We were looking to understand refugees’ financial integration experiences on their own terms, but also to provide some clues for how resettlement agencies and other groups in the larger Dallas community might help ease some of the challenges around integration.

We had three central research questions:

• What are the common phases of financial transition for different groups of refugees? (We looked at men and women, different age groups, and different nationalities.)

• What kinds of financial tasks are important during each of these phases?

• What kinds of struggles do refugees face in completing these financial tasks during each stage?

We explored these questions through semi-structured, in-person interviews of 1.5–2 hours each, conducted in English, Arabic, Dari, Farsi, and French, according to the preferences of respondents.

Refugees’ experiences and backgrounds are very diverse, and our small study is not representative. We spoke with 29 refugees from Afghanistan (14), Iraq (12), Congo (2), and Syria (1). Many (15 of 29) came to the United States on Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs), being given the opportunity to resettle because of the risks posed to them by working with the United States government in their home countries. For families coming on SIVs, at least one family member tended to be highly educated and have some working knowledge of English prior to arrival in the United States. More details on our methods can be found in Appendix A.

Key Findings

After two or three years, many respondents had not yet regained the level of economic welfare they experienced before their lives were disrupted.

Every respondent’s story was different, but many of the refugees we spoke with had lived comfortable, middle-class lives in their home countries. Even if their overall earnings were lower than in the United States, they tended to live in family homes with far fewer expenses. Often, the mother of the family did not work, because it was not necessary. Respondents talked about having more slack in their budgets and more time to spend with family and friends in their countries of origin. In the United States, only some were able to enter quickly into careers befitting their education or professional training. Instead, most started off working in hotels or supermarkets, earning relatively low wages.

Over time, many of them transitioned to different jobs, though the jobs were not necessarily high-paying. As depicted in Figure 1, many were beginning to feel they were on an upward trajectory in the United States, but that was much less common if they experienced a health shock, a topic we will talk more about later. Also, if respondents were able to move into more professional careers, economic progress accelerated dramatically.

Figure 1: Typical economic trajectory of a refugee respondent. The dashed lines indicate alternative paths for those who were able to work in exile or upgrade their careers or who experienced a health shock.

Two men conveyed these contrasts particularly well. Mahmood3 finished university at home in Kabul and worked in a US-funded recovery program, first as a driver and later as an operations supervisor. When he came to the US, the IRC helped him find his first job, repairing cell phones. He was making $10.50 an hour.

One day, he got to talking to a Brazilian neighbor about work. The neighbor mentioned his own job as a network technician working on installing Cisco networks, something Mahmood had actually studied a little back home. After four days of training, he started working full-time for $34 per hour.

He has accumulated a number of certifications in Cisco as well, placing him on a trajectory towards a six-figure income, he believes, within another year or two. “I don’t think any Afghan has the kind of job I have. It’s a very good job with good pay,” he told us. At the time of the interview, he was saving around

$5,000 per month, which he hoped to put towards a house.

Khairo had a very different story. He had been a supervisor in the Iraqi government. Now in his late 50s, he works at Walmart. “I don’t like my job at Walmart. They don’t treat us well,” he said. One day, Khairo fell at work, and the company called an ambulance to take him to the hospital. Shortly after, he got the

bill: $21,000. He then felt trapped in his job with this debt hanging over his head:

"I’m afraid of quitting. See, I’m trying to get US citizenship, but I’m afraid that if I quit without paying the medical bill, that might have an impact on my file. I’m also stuck because of my loan to pay for my car and its insurance."

Khairo was surprised it had taken him so long to find his economic footing in the US. He started part-time work as a home health aide and was working towards a certificate in that at the time of the study, but had to pass the GED before he could be certified. It felt daunting to him at this stage in his life, but he wanted to find some way to move forward economically.

The more common pattern we observed was a slow climb. Many had long periods where they felt stuck and were living just within their means, saving only small amounts. They might experience small upward bumps in income by changing jobs from those that pay $9 per hour to those that pay $11, for example. Bigger boosts came when they were able to either acquire new skills or certifications, like truck driving, car repair, or interpreting, or have their existing skills recognized by a new employer. Recognized skills allowed for quick, stepwise bumps up to new levels of economic well-being. Without one of those bumps, few felt they could meet their big financial goals, like buying homes and being able to send more money to relatives back home.

While landing a well-paying, professional job appeared to be key to long-term financial success, many struggled to translate their educational attainment abroad into a useful job in the US. Investing in formal education—whether a GED, undergraduate degree, or master’s degree—felt impossible for many young refugees. When they arrived in the US and realized how much traditional college and graduate programs cost and how expensive it is to survive, the need for an immediate income typically overtook educational ambitions.

Lana’s education was disrupted when her family fled Iraq for Syria and then to the Emirates, Turkey, and Erbil. By the time her family came to the US, she had just passed her eighteenth birthday and could not enroll in high school. Two and a half years later, her mother still wanted her to get her GED and take some college classes, but Lana felt the family needed her to be working. There was not much time for anything else.

Amy arrived in the US with a bachelor’s degree from Iraq and was enthusiastic about starting a master’s degree. A couple of months after arriving, she went

to the University of Texas, Dallas, to inquire about enrolling:

"When I went to UTD, I could not believe how much I would have to borrow. I could not believe the tuition! I did not know what jobs I could get. I was completely confused."

She eventually found a patchwork of jobs and is taking classes in medical billing, giving up on the idea of doing her master’s. Advancing her education the way she had planned was too risky:

"I’m not stable here. That’s why I was hesitant about taking a loan to get a master’s degree. I first need a job with good money. The master’s takes two to three years, and I can’t depend on the master’s to get a job. I need the job first. It makes me too worried. I am not an expert here, I don’t want to face some problem that I can’t get out of in terms of financial issues."

Refugees were surprised by how difficult economic life is in the United States.

Many of our respondents from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria were middle-class in their home countries. They had decent jobs and—most importantly—minimal expenses. They typically lived in shared family homes that were owned outright, did not need cars, and found other expenses to be minimal and mostly on things that were not necessities. The United States, by contrast, was a much more expensive environment. Respondents were surprised that rent, cars and car insurance, childcare, food, and regular bills consumed so much of their earnings. One respondent, Charles, explained:

“It’s not that we were that rich in Iraq, but things were just easier, more comfortable. We received our salary in cash, and there weren’t so many bills to anticipate—no rent since we owned the house, no car insurance, no bank asking me to pay my credit card, no fees for school. Basically, our only fixed payment was for utilities, which wasn’t even much. And so, when it came to food, going out, or even spoiling ourselves, we didn’t need to calculate, we just went for it and we knew we’d have enough for whatever it was we were buying because we knew what our salary was.”

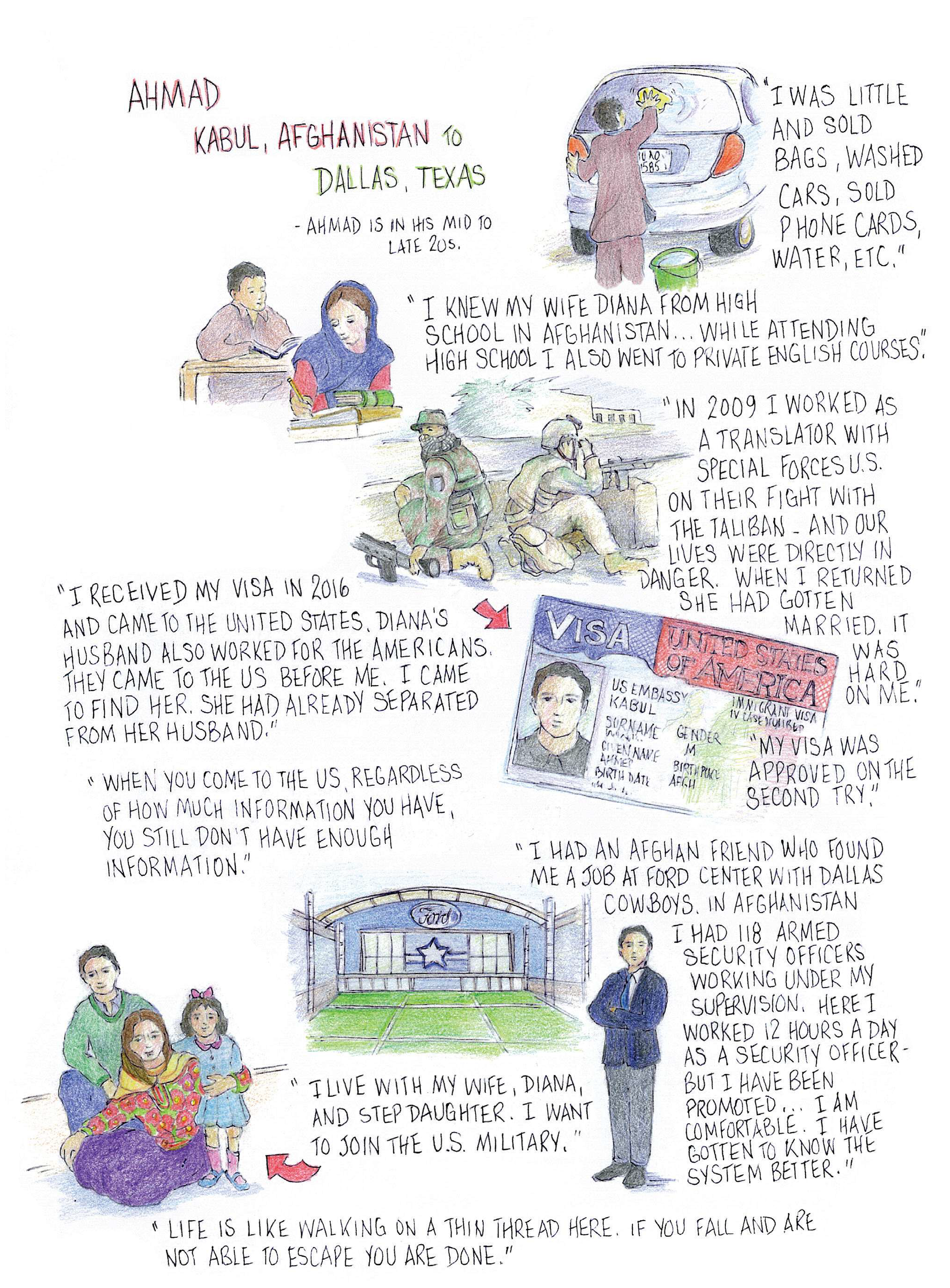

A number of others echoed this sense of living close to the edge. For some, rent alone consumed 80 percent of their monthly earnings, leaving little wiggle room for other expenses. They worried that some unexpected expense—a car crash or breakdown or a medical bill—might wipe them out. Others worried about losing their jobs. It seemed much easier to be fired or laid off in America than back home. “Life is like walking on a thin thread here,” one young man, Ahmad, told us.

It has taken many respondents longer than they expected to achieve the kind of comfort and stability they expected. This is the source of significant anxiety for some respondents. Amy explained:

"I don’t have a solid stand. I am always thinking of my long-term plan. When will I buy a home or small apartment? I don’t own anything in this country. I need a job that pays more. I don’t always get the hours I need. I want a full-time, stable job. I need that job this year. I don’t want to be so hesitant and uncertain. It makes me worry."

Many respondents, especially men with children, worked multiple jobs as a result of these feelings of being overwhelmed by expenses and being vulnerable to the unexpected. They often had one main job, but worked on Uber, Lyft, or Amazon Delivery on the side to make ends meet. Some reported working extremely long hours. In addition to feeling as if they were always working, the work sometimes felt degrading compared to the more professional types of jobs they had at home. Murtaza, a 28-year-old Afghan, explained, “I know people who have returned to Afghanistan. If you have good jobs at home, you won’t enjoy loading boxes here.”

A number of respondents talked about the work culture of the US being a source of some culture shock. The discipline of strictly clocking hours, the need to schedule days off well in advance, and the perceived ease of being fired from work all seemed new. It seemed that Americans centered their lives around work, rather than people, in a way that felt unfamiliar.

“Here it is mandatory to work to have a house, which is very strange for us.”

–Mickael and Gabriella

“My husband was very depressed [when we first came]; he felt life in the US was all about working and praying, with no time for a social life.”

–Alexandra

Many arrived with important skills for financial success, among them the discipline to save and the ability to cultivate sources for low-cost borrowing among their social networks.

Prior to leaving their home countries, many of our respondents had saved substantial sums. Many lost their physical assets during the conflict, depleted their savings during exile, or made the conscious decision to leave their assets behind to help take care of their families, knowing it might take some time before they were able to send remittances from the US.

Ehrar, for example, started working with the US military in Afghanistan as soon as she finished university. Within just a few years, she saved enough to buy a plot of land for $9,000 and build a home for her family with another $35,000 in savings. She felt compelled to take care of this important need for her family before she came to the US. She has six sisters, five of whom are still living at home, and her father hasn’t worked in four years. Though she is not yet on stable footing in the US, she manages to send $450 home every month. Ehrar came to the US with only about $200, but that was not because she was poor at home nor because she had been an undisciplined saver.

Many others also arrived with very little, despite histories of saving and accumulation. Mickael had been a government worker in Iraq who had to sell his car and use most of his savings to ransom his son after he was kidnapped. Another family, as well, lost everything rescuing the husband after a kidnapping in Afghanistan. The rest of the family assets—plus borrowed funds—were used to help the entire family flee to Sri Lanka.

In addition to arriving as skilled savers, many also had robust, transnational social networks for low-cost and flexible-term borrowing and lending.4 This ended up helping a number of refugees who faced financial challenges early in the resettlement process. One respondent, for example, was able to borrow $3,000 from new Afghani friends in the US to buy his first car. Another respondent borrowed $2,000 from a neighbor to go back to Iraq after her daughter gave birth to the first grandchild in the family. She promised to pay the neighbor back as soon as her family got their tax return, a practice that appeared to be relatively common among the refugees we interviewed.

One family was going through an economic crisis when we visited. The husband had been laid off work and was yet to land a new job two months later. They were getting by on loans from friends—mostly other Iraqis and Syrians—to pay rent and buy basic necessities. Others talked about specific, wealthier friends and relatives who occasionally simply helped out by paying rent or sending money when they perceived things were not going well. This seemed to make people feel more confident in facing their financial challenges in the US as well as assured that they could help if an emergency happened in their home countries that required them to send money.

Those who were doing much better and had reached some level of stability felt proud to be lending to others who struggled. Mahmood, who is doing quite well now, explained:

"I have lent around $10,000 to friends who have come after me to the US. They needed to buy cars or had to send money home and asked for help, so they borrowed money."

While most would prefer not to need to borrow money, our respondents appeared unashamed to ask for this kind of help:

"It’s culturally accepted [to borrow money] in our society. If my friend is in trouble, I will definitely help them. And if I am in need, they will help me. Most of my friends are from the same place in Jalalabad. We have a small network. More than 70 families live in this area. There are at least 10 friends that I can easily ask for money." –Shakeb

We observed a general hope among many who borrowed money when coming to the US or who have been borrowing as they rebuild their economic lives to one day become lenders. However, we did not observe many people who have yet made that transition after two or three years. Similarly, while many hope to be able to send remittances home, only some have achieved this so far. In many cases, respondents did not feel like they were financially able; in others, the needs at home were so pressing that refugees were making significant sacrifices to send money via Western Union to family—particularly elderly parents—back home.

A key attribute of those who are thriving now was the ability to overcome social fears.

Starting a new life in a new country, particularly one where you do not speak the language or understand how basic things—like the bus system and washing machines—work, is intimidating. There is so much to learn. Refugees fear they are going to be scammed or taken advantage of; they must both rely on the kindness and generosity of strangers and face difficult situations on their own. This takes enormous courage but also opens up many new possibilities.

Alexandra had been a high school economics teacher in Iraq before fleeing Baghdad for Jordan, then Syria, and then Turkey before finally getting resettled in the US in August 2015. She explained what it was like to work:

"My first job in the US was very different from any job I had done before. I was working in a hotel. I used to be a teacher in Iraq, and in Syria I was working with the UN, so I really wasn’t used at all to doing physical work. I never imagined myself cleaning up for others. In Iraq, we had people cleaning for us!"

"It was really tiring and I felt a bit insulted, perhaps. But I quickly adapted! I didn’t want to be afraid of life anymore. Things were just different here. And when I got my first paycheck, I felt so independent that I focused only on the good aspects. My fears broke down. I stopped being afraid of people’s perceptions—about my Hijab or my bad English. I have never felt discriminated against. I realized that all these fears were just in my mind."

We visited Alexandra only a few weeks after she and her husband moved into the new house they purchased with a mortgage. It was Alexandra who led on the real estate negotiations:

“We had to take a $260,000 loan to get this house. I thought it would be difficult, but the bank and the company were very supportive. I managed to negotiate the price down a bit. . . . I think they chose me because of my self-confidence. Americans like to see people like us who work hard to improve themselves.”

Now that she was driving and working, she was able to change jobs a few times. She was working in a mall when we interviewed her, and she particularly liked this job because it allowed her to practice English. She was beginning to make a plan to open her own restaurant one day. She feels successful:

“My husband wasn’t really as motivated as I was. . . . He’s never really had the same self-confidence I have. He is afraid of everything, he thinks everything is destiny and is already planned for us. But I’m not like that.”

Mustering up this courage was difficult for some respondents. Women who were not yet working, for example, seemed particularly isolated and afraid. This fear created some self-perpetuating challenges. They were not working, so they found it hard to practice English. They were afraid of working because their English was not very good. Some were still hesitant to learn to drive, as well. Those women, like Alexandra, who did find ways to get out into the world—through driving, work, and making a friend—seemed to gain confidence, feel more at home, and have higher hopes for their futures.

Amy told us:

“Getting a job was the best victory for me. Because of that, I started to learn to drive. I started to see the American world. . . . I started to apply for community college and to take English classes. I was able to actually drive to classes. I was working, taking classes, driving. I started jumping ahead. I hadn’t taken classes earlier, because I was afraid to drive. After driving, that’s where I had more confidence, like ‘Wow!’ I remember the first time I took my mom and my friend to the mall. I felt so good. I started to change and was much more optimistic. Everything was okay with me when I was able to drive. I was able to go and hang out with my friend, go nearby places, discover town. . . . Then she did not know anyone either, so we started to discover everything together.”

A few of the young women we met who came to the US without older male relatives found learning to drive to be particularly harrowing. Who would teach them? Classes were expensive. One of them, Erhar, had resisted driving as long as she could, but late one night while trying to return from work, her bus was canceled. She had to walk home alone, terrified:

“I walked for one hour. It was scary. Even now I think how I did it. When you are in a situation sometimes, you have no choice but to overcome it. . . . I was asking myself, why did you come to this country alone? I told myself that was my last night left on the street. I had to get a cheap car and learn how to drive. I asked my friend to help me learn how to drive. I bought a car and she showed me for two days and after that, I just drove with my permit on the streets. There were times I drove the wrong way on a one-way street and trucks signaled. I found a way to get out of their way.”

Another young woman, Lana, played the role of the courageous, outward-facing member of her family. Her mother also recognized how valuable Lana had been in helping the entire family navigate the transition. Lana was proud of her role, but also felt that it was sometimes a burden:

“My manager at Starbucks would get frustrated with me. I missed work quite a lot. See, my mom was having health issues and needed to go to the hospital. Her arm was not moving. I don’t know what happened. My manager told me that I’m an adult and not responsible for her. He didn’t understand. Yes, actually, I am responsible for her. I am the one who speaks English. I am not afraid to talk to people. I am not afraid to call the police. I am not afraid to talk to the manager. My siblings, my parents, they just can’t do that. I am the one who can manage things. In this family, I am the driver, I’m the shopper, I’m the breadwinner, I’m the everything! . . .

Now, I really need my sisters to step up. I need my sisters to be more brave. They are shy. They are scared. That’s why I think it’s so important that my sister gets a job. She needs to be out in the world.”

Finding courage and the tools to navigate Dallas has been transformative for many respondents. It’s also essential for learning some of the complicated ways things work in the US. So many things—like finding new jobs, or really understanding credit cards—cannot be fully covered in training alone. Khairo told us how he found these things at first to be very intimidating and confusing, but he just decided to speak up and ask questions:

“Now, I am the king of the bank! Every three days I used to go to the bank, to Capital One. The guys there are amazingly patient. Some other refugees are afraid to ask, but I always just think, ‘C’est la vie!’ as the French say.”

For the most part, respondents had a good grasp of the basics of how to navigate the US financial system.

Much of the respondents’ grasp of the financial system came from IRC’s training, but other knowledge was acquired through experience and by asking questions, as noted above. Many respondents remembered being overwhelmed by the new systems when they first arrived in the US. They recalled IRC staff taking them to cash their first assistance checks, so they learned that process. Many check-cashing facilities also offered international remittance services through Western Union, so they were able to locate those services for the future. Some banks presented their offerings at orientation sessions organized by the IRC, and refugees typically chose to open accounts either at those banks or where friends told them a staff member spoke their language.

“I really didn’t need a bank account right away, but when I got it, I went to Chase. We knew there was an Arabic speaker there. That’s just good to know, in case something bad happens, you just want someone you can ask questions.” –Lana

The IRC trainings around the financial system were praised by most refugees, with some exceptions from those with very high levels of education and English, who thought they were rudimentary. For many, though, the training seemed to be at the right level and pace.

“IRC trained us about opening bank accounts, finding jobs, paying bills, and kids and their school. They told us to pay rent on time. We learned that here they fine you if you miss payments. They told us to not keep money at home. They told us if you lose your card, call your bank.” –Azra

“Everything is difficult to understand: how to cash in a check, how to use your account. In my country every month there was an accountant who came to the office and handed us our salaries in cash in an envelope with a payroll sheet. That was the only system we knew.” –Khairo

The credit scoring system was new for nearly everyone. Most of our respondents talked about learning how important it was to build a good credit score, mostly so that they might get a mortgage one day. While many remembered credit scores being covered in the IRC orientations, others felt it wasn’t covered enough, or things about the system simply didn’t make sense until they started using credit for the first time.

“When I first used my credit card, I thought that was free! I had no idea about interest rates. I had never even thought about it. After one month, my bank called me and said I needed to pay back, with extra! But I didn’t get upset or sad. We all need to make mistakes to learn. As soon as I found out, I informed my friends on the WhatsApp group so they wouldn’t make the same mistake. They told me about the Credit Karma application. I’ve downloaded it, and now I check it very often to see what my credit history looks like, to understand what makes it look good and what doesn’t. I really enjoy it.” –Alexandra

“My bank also taught me everything about the credit system. They said that if I have $1,000 in credit, I should only spend $300. Right now, my strategy is to only use my credit card to cover gas—about $25 dollars a week—and I always pay the day before the due date. I managed to raise the level of my credit four months ago.” –Tom

Gaps in knowledge and comfort with the financial system came mostly from the kinds of issues that refugees are unlikely to encounter early in their resettlement.

Part of the trouble with financial system training very early in the resettlement process is that so much information about everything needs to be taken in during a time of big transition. One refugee remembered that the International Organization for Migration (IOM) tried to provide some training on the financial system, but none of it stuck with him:

“Imagine yourself coming from a city that is quite modern but where insurance, credit cards, etc., simply don’t exist, and that a guy tries to explain these things to you in 30 or 90 minutes! I honestly can’t remember, and I might have skipped some parts—everything about Medicaid, insurance, credit scores. . . . How could that be efficient? At the time, when they were talking about ‘credit scores’ I couldn’t make sense of anything they were saying, because I was still imagining I’d be paid in cash! It didn’t make sense at all to me.” –Ali

Another challenge is that not everything that gets covered—or could be covered—can be immediately put to use. For example, only after six months to a year might refugees be ready to start thinking about understanding how mortgages work and the necessity to start saving up for a down payment. In Table 1, we outline the key financial tasks refugees reported that they were trying to accomplish at different stages of their transition. We list the key skills and information needs related to each of those tasks, suggesting when the tasks are typically undertaken and when it might be appropriate to introduce the new information and skills.

Without a way to regularly communicate new training topics to refugees after the first few months in the US, resettlement agencies find it difficult to help with these issues in a systematic way. This may be a space where social media could be particularly helpful, providing some training by video and advertising occasional trainings—such as on tax preparation and Medicaid renewal—that arise after the initial period of resettlement. The IRC offers support on these issues, but it’s not clear that all refugees hear about these opportunities.

Dealing with healthcare expenses and insurance appeared to be a major source of financial strain and stress.

When refugees arrive in the US, they are enrolled in Medicaid (government-provided health insurance) for eleven months or Refugee Medical Assistance (another form of subsidized insurance) for eight months. Most had positive experiences with Medicaid, but many did not understand that this insurance was temporary or keep track of the expiration date. Some did not realize they needed to reapply if they were still eligible, and what to do if they were no longer eligible. They typically found out through an expensive bill:

“I didn’t know when my Medicaid ended. I got sick once, and went to the hospital. I later got a $4,000 bill from the hospital for the emergency room expenses. Another time, I went to the emergency room, and the insurance wouldn’t cover it, so they sent me another $4,000 bill. I didn’t want to pay that. I sent my proof of income and told them I couldn’t pay it. They said it takes up to eight months to confirm the proof, so I am still waiting on their response. Why get insurance if I have to pay $4,000 for a hospital visit?” –Shakeb

“A few months after I came here, I went to the hospital once, and we got a $12,000 bill. We still have the bill. We weren’t aware the Medicaid was cut off because my husband was working somewhere that paid him $12 per hour. We lost food stamps and Medicaid because of that.” –Fatima

“We got rejected by Medicaid because we didn’t apply on time after our Medicaid expired. They would charge us a fine if we applied late. We weren’t told that if the insurance given by IRC ended, we had to reapply ourselves and, if we applied late, we would face a fine. None of this was given to us.” –Marzia

“Since IRC stopped covering us, we lost Medicaid. That’s our main problem right now. We have no other issue here in the US. We can rely on ourselves for all the rest. But it’s insanely expensive here to go to the doctor. It’s a luxury to go to the hospital. We knew before coming here that it would be like that, but still, we thought we’d find a way to get around it.” –Aziz and Sarah

Table 1: Financial tasks and skills needed over refugees’ phases of transition

Children remain eligible even when adults lose coverage. No families we spoke with found it difficult to renew coverage for their children, and said that the process was relatively straightforward once they understood the deadlines. Many adults, however, were not sure about alternative options for health coverage. Even when they understood these options, the very high cost of health insurance made some choose to be uninsured. Those who then had healthcare emergencies or who were trying to manage costly chronic conditions were facing serious financial hardship because of these issues.

“I can’t apply for insurance because sometimes insurance can cost you more than you’re earning. . . . After my Medicaid got cut off, I went to speak with the Medicaid people to persuade them to extend my Medicaid. They extended my wife and my children’s insurance, but I don’t have it for myself. It’s like the insurance for car and health goes in the air and you get nothing in return.” –Hesam

“I don’t have health insurance at the moment. I didn’t take it from work because without that I can’t save.” –Ahmad

“My parents have health care through Medicaid, but I don’t have children, so I can’t have Medicaid. Healthcare is so expensive here. I need to just die at home, because healthcare is way too expensive. I can’t go to the hospital.” –Lana

“Right now, my parents and myself, we don’t have insurance. We can’t afford it. If we are sick, we cannot go to the doctor. We can’t have our teeth checked. My dad has back pain, but the medicines do not work. He can’t go follow up with a doctor, because the Medicaid stopped. It’s now just for the kids.” –Raha

“Everything is okay, except for Medicaid. What’s the deal here? I need to choose between a roof over my head or a slow death? Because of diabetes, my wife and I have problems with our teeth. They’re falling out, and it costs about $2,000 to replace just one tooth. Even if you don’t want to replace them, it’s about $180–200 dollars just to have it pulled out by a doctor. . . . I thought I was ending a nightmare when I left Iraq, and here I find myself struggling again. If I had known, I wouldn’t have come to America, I really had no idea. IRC said that the only solution is to go in some of these states in the north where we can get better health insurance.” –Charlie

While there are some low-cost healthcare options in the area, including a sliding-scale clinic near to the IRC office, only some of the refugees we met (typically those with longer-term relationships with the IRC) knew about these options.

Co-nationals were an important source of information, resources, and job connections, but some refugees push away from their co-national community.

Nearly all of the refugees we met were resettled in Dallas because they had a local tie, a close friend or relative who could help them navigate their transition. Those US ties and other co-nationals who shared a language and culture played an essential role in helping refugees settle, particularly during the first few months. They provided advice about where to shop, how to open a bank account, even about how to do laundry. They helped many refugees get their first job or transition to a new job, after their initial placement facilitated by the IRC. Some refugees participated actively in social media groups of co-nationals (or more broadly of refugees with the same language), which you will read more about below.

However, we also saw many refugees deliberately push away from the co-national community. A few found the quick intimacy of co-nationals they didn’t already know well to be suspicious. Were they being taken advantage of?

“We don’t really spend much time with other Afghans. We’ve met a few, but one family we met early on, it’s like they helped us, but then when a new family came, they forgot about us. It felt like maybe they were trying to take advantage of us. I heard that there was this person who was helping another family, like translating for them when they needed to do things like go to the bank. But then he took a credit in their name. I heard it was like $5,000, and that family was stuck paying off that loan.” –Raha

“A young Iraqi I met at IRC – he’d been there a year or two before me – started speaking to me there. He told me he was also looking for a job and we started seeing each other. He spoke English better than me and he knew how things worked in the US. From the beginning, I was a bit afraid, suspicious. After 2003 in Iraq, we all became unable to trust one another. And in the US you’re even more worried. Anyways, so this young Iraqi guy, after helping me a bit, started asking me for money. He helped me pay for the internet online and understand the health insurance. I would give him 10, 20 dollars. One time, he asked for 100 dollars and I had to give it to him. I needed him for many things, I wasn’t confident I’d do things correctly on my own. Part of me wanted to help him but part of me didn’t. I think he offered these ‘services’ to other refugees. But within a year, I stopped asking him for help, I didn’t need him anymore. I stopped seeing him.” –Khairo

For others, the assumed intimacy and intrusiveness were overwhelming:

“I am not on any of those WhatsApp groups with other Iraqis, where people sell themselves, their problems, their intimacy.” –Tom

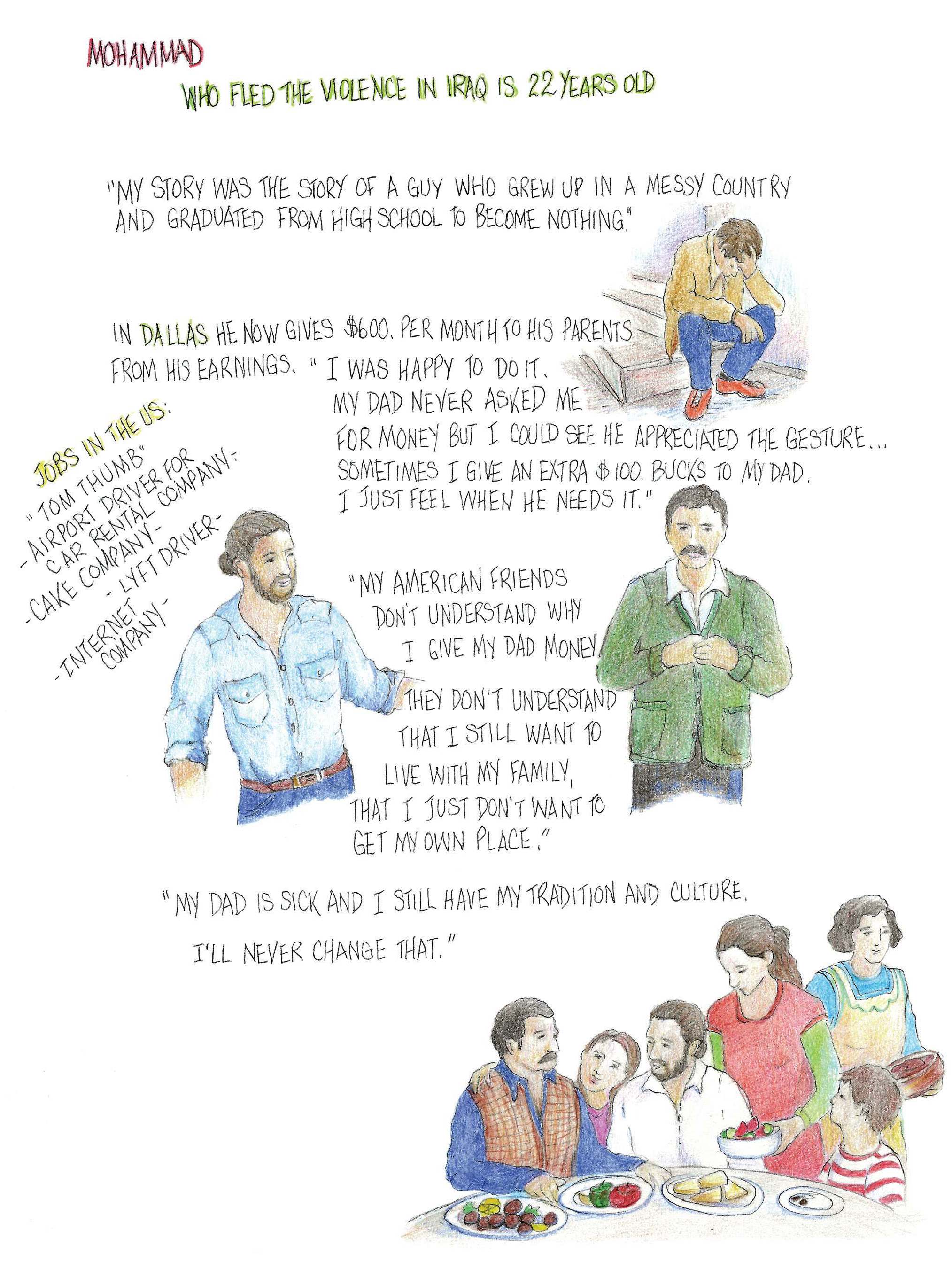

“I didn’t enjoy working at the airport because of all the Arabs that were there. I find foreigners [Americans] better. Arabs talk about one another too much. People ask you for the price of your phone. They asked me whether I helped my dad. Of course, I do, but how is that their business? They were just too intrusive. I hate that mentality.” –Mohammad

More often, though, respondents simply felt the cultural norms of their home country overly restrictive. Moving to the United States was an opportunity to create a new identity, to make new kinds of friends, and to make independent decisions about some aspects of their lives.

“I don’t even go to the mosque here. I don’t like to see people there. I don’t even pray, so why would I go? You know what, I even go clubbing! [laughing] Right now I even have an Israeli friend! I don’t care; we’re all humans. The color, the religion—it doesn’t matter. I don’t talk about nationalities but about human beings. People like this about me at work. I live on the principle of being honest, of doing the right things. And I gave this to my kids. Now they have friends from the US, from Mexico, Nepal, Syria, all over the world!” –Tom

“I live among Indians. I didn’t want to go among Afghans, I don’t like the culture the uneducated Afghans have created here. Islam is not against women working; Afghans judge when you allow your wife to work or to drive so I try to stay away from them.” –Murtaza

Other immigrant acquaintances and IRC mentors facilitated economic integration.

As hinted at above, other acquaintances and friends who shared the immigrant experience were often important sources of information, support, and friendship. Making friends with Americans could sometimes be difficult, it seemed, but other migrants shared much in common, without some of the baggage that comes along with communities of co-nationals. Many mentioned how helpful other, patient immigrants were in filling out bank paperwork and even in finding new jobs.

"I met a guy in my work whose name was familiar. I asked if he is Indian. He was from Nepal. I felt a joy that there is another Asian at my work."

–Shakeb

"Most of my friends are other international students. I have friends from Afghanistan, also Ethiopian and Singaporean friends. I just put up a post here at college looking for a roommate. I hope to find an international student roommate." –Ehrar

Particularly since meeting native-born Americans was sometimes difficult, the few refugees we met who found American mentors through the IRC were extremely grateful for these connections. The mentors helped open up Dallas in new ways, introducing refugees to interesting places like museums. One helped a refugee get into a training program for high-end vehicle mechanics. They advised them on difficult problems, like what to do about overwhelming medical bills. Murtaza described his family’s relationship with an American mentor:

“The best thing IRC did for me was introducing me to a woman who volunteered with them and who has become my mentor. She was supposed to volunteer for six months, but we are still in touch with her. She takes us to her farm, visits us at our house, and when I am busy working, she takes my wife and kids to their appointments. I feel so grateful to have that connection here.”

A few key pieces of technology play outsized roles easing economic integration.

In addition to depending on co-nationals, other migrants, and advice from IRC, many refugees are successfully using technological tools to help them learn new systems, communicate, navigate, and earn extra money. While refugees used some of these tools in their home countries, others, like GPS, were new. Mastering them was something to be proud of, something that helped open up new opportunities. A few of the key technologies, how they were used, and how respondents spoke about them are outlined in Table 2.

YouTube was a helpful resource for many to learn English words and concepts, where they could also see visual cues. It could also teach important skills exactly at the moment they were needed.

“Sometimes I go on YouTube and watch videos that teach English words. Most of my learnings are from those videos. I haven’t tried online classes or courses. I search English words in YouTube; I search for verbs and tenses.” –Kefaya

“It was very difficult to write my first check in English to pay my bills. I wasn’t sure what to do so I checked it on YouTube! I knew YouTube from home.” –Khairo

“It wasn’t hard to learn the new financial system. I had watched videos on YouTube.” –Shakeb

Google Translate was a lifeline for many respondents negotiating complicated interactions, even for those whose English was pretty strong:

“I wanted to get a card from Capital One. It is part of being at home here. I went with my dad to the office, and we filled out an application. Those forms are complicated, but we just use Google Translate on the phone. It helps me so much!” –Lana

“I’ve sent a text to our landlord using Google Translate, and she said we could pay by the 20th of the month.” –Abed

“I had never driven before. I took so many practice tests online. I would use Google Translate to take them on my own.” –Alexandra

General Google searches are also very useful, pretty much the same as they are for any American:

“I do a lot of research before deciding about something. There were many things that were new here, but I read, I Google, I research, and I make sure I know enough about the things I don’t understand.” –Ali

“It wasn’t hard to learn about new financial systems here. I pick up things very easily and very quickly. I Google everything I don’t know about. I always find solutions to my problems, I know how to do it.” –Lucky

GPS/Google Maps was new for many respondents and proved to be tremendously helpful in getting around and remembering where important places were when everything was new and unfamiliar. Many reported how important it was that friends showed them how to use GPS. Learning to use GPS in the phone was viewed as an important skill, one that had to be learned and that not everyone in the family necessarily acquired:

“In Afghanistan finding places was easier, because we know how to get around. Here without GPS I am lost. I can’t do anything or go anywhere. The biggest challenge was finding places. To me everywhere looks the same. Think of those who can’t speak English well! . . . I always put the nearest everything on my GPS. For example, the nearest Walmart, nearest hospital, etc. In my Uber, sometimes the elderly passengers say they used paper maps. I think I could never be able to get around with those maps.” –Murtaza

“In the beginning, my husband didn’t have a phone with GPS. He had a hard time understanding. He didn’t speak English well. Now he knows how to use GPS. With his first job, he went with another Afghan who showed him the way. He learned how to clock in and clock out. That Afghan friend helped him a lot. After a while, that friend left to another job so my husband had to learn his way around on his own. He would get lost at times because he would put a wrong address on the GPS.” –Azra

Social media was an important way that refugees kept in touch with family and friends at home and scattered around the world. This made it possible to, for example, borrow and lend money over long distances. But it was also important for refugees building community in Dallas. While some refugees resisted these kinds of co-national social media communities, others embraced them wholeheartedly, finding that they were a helpful resource for information and mutual support. Alexandra explained:

“We have plenty of social groups, on Facebook, WhatsApp, Viber. . . . A lot of Iraqis and Syrians use them . . . to share any extra food we have, things we don’t need anymore. We don’t expect anything back; we all do this voluntarily. Last week I bought this lamp, and it was a really good deal so I posted about it in our WhatsApp group. Even if it’s nothing special, I still like to tell others about these deals, just in case someone would benefit from them.

This group is only for women; it’s the one I use the most. It’s been here since I moved here. I’m not sure how many participants there are in this group. Some have been there for a very long time, 10–20 years, and some are new like me. But it’s only for people in Dallas.

One time, a lady wrote to this group. She had lost her husband, and she had four kids. She couldn’t pay rent anymore. We all gave five to ten dollars, and eventually it got up to 500 dollars in total. It’s been a year now, and it is still through these very small contributions that she pays rent. No one has signed up to support for the long term; different people give at different times. Sometimes we give two, three, five dollars. I personally don’t like to participate in more-organized loan groups. Our lives aren’t stable enough yet to do that. What if we suddenly lose our jobs? But some Iraqis who’ve been here for a long time are very successful, so they invest in our community here. They help us plan our life ahead.

I sometimes use the WhatsApp group if I need a translator to come with me somewhere, or if I need a recommendation for a doctor or an idea of their prices.”

Another respondent, Charlie, talked about a similar (or perhaps the same) group. His wife followed the group conversation and filled him in. He pointed to many of the same types of functions: sharing extra food, contributing small amounts to help someone who needs extra money. But he also talked about patronizing refugees who are trying to start new businesses. He seemed to draw emotional comfort from belonging to this group:

“One time, the group gathered money to send it to an Iraqi lady in Turkey who had lost her father and needed to send him to Iraq to bury him. We also gave money and sent it to other Iraqis in Turkey who helped the lady organize the burial. No one expected to be reimbursed; this is all just voluntary help, heart to heart.

One time a woman couldn’t pay her rent anymore, so she was asking on the group about whether or not she should move to California, because she would have better health insurance there. She had a sick daughter and needed to buy drugs for her, and her Medicaid had stopped, just like it did for us. An Iraqi lady who had been in the US for much longer actually told her to move into her house, and she did!”

Labor platforms, especially Uber, Lyft, and Amazon Delivery, were helpful ways for refugees—especially men—to earn extra money or fill gaps between other jobs.

“I work at the car service and also work for Uber or Lyft on the weekends. The new place we moved to is much more expensive, so I need to work more.” –Murtaza

“I had started thinking of working as a taxi driver, but before quitting my job at the airport I wanted to make sure that I’d make enough money. I took three weeks off and tried out Lyft—it’s like Uber. I made $1,100 in only one week! So I picked it up in September 2017 and quit my job at the airport. A month later, I started working at a cake factory—a friend of my dad’s was working there. I worked there for four months—they paid $11 per hour—and I continued working with Lyft part-time.” –Mohammad

“Let me tell you one thing: Here in the US, you have jobs. If someone wants to work, he can. . . . Here there’s no excuse for not making money: there’s peace and there are jobs. If I ever had a problem with my delivery job, I can find a new one within two days! I can even just Uber with my car!” –Aziz

Table 2: Technologies that accelerate financial transitions

Ideas for Strengthening Transitions

What should the IRC, other resettlement agencies, and community partners do to further strengthen and accelerate financial transitions of refugees? This research suggests a number of promising possibilities, many of which require little money.

1. Embrace technology.

During orientation sessions, resettlement agencies could specifically introduce the key technologies already playing roles in easing economic integration, such as Google Maps, Google Translate, YouTube, WhatsApp, and on-demand labor platforms. Some of the technologies—like YouTube—do not need much of an introduction, but others, like Google Maps, may be new and require some practice to become comfortable using them. In Germany, the IRC has developed a partnership with Care.com to help refugees access work as caregivers. A similar program that helps more women enter the workforce, especially on a part-time basis, could be helpful in the US.

2. Help women learn to drive.

An important barrier for women’s integration is learning how to drive. In addition to helping refugees access affordable, nearby English as a Second Language (ESL) courses, might refugee resettlement agencies help them identify appropriate driving courses? Might local partners sponsor such an initiative and help give women safe environments and coaches as they practice and build their skills? As with ESL courses, these will be more accessible if they are near women’s homes and offer child care during sessions.

3. Facilitate more “firsts.”

Respondents told us how powerful it can be to overcome fears and force themselves into positions where they have to try new things and gain new experiences. While some do this on their own, refugee resettlement agencies can introduce the more timid or cautious refugees to many new “firsts” with the support of volunteers, mentors, or even other refugee buddies. In this way, new refugees share the risk and take on difficult situations with the help of a confidante. These kinds of experience may help build confidence and in the long term ease some of the burdens older refugee children feel as they help their parents navigate the US.

4. Support young people carrying the burdens of transition.

This study demonstrated the enormous role that young refugees are playing in helping their families through the early years of transition. Resettlement agencies could more formally recognize this role, by making sure that teenage and young adult refugees participate in most of the orientation activities, including additional activities providing more tailored support to them. Taking the time to listen to their specific feedback and viewing them as partners might help them fill their roles in the family even better and manage some of the stress that comes with the roles they play. Some of these young people give up on their ambitions to study and advance their own careers because the opportunity costs of leaving employment are too high for the family to bear. Could resettlement agencies and community partners help them navigate these competing roles more successfully?

5. Develop a social media strategy to maintain communications.

Refugee resettlement agencies could better share accurate, timely, and helpful information with refugees through a well-crafted social media strategy. The main way that IRC currently communicates with refugees outside of the early resettlement period is through email and hard-copy flyers posted at their office. Phone messaging, WhatsApp, and Facebook could be much more powerful.

A moderated Facebook group for resettled refugees would be an ideal way to leverage a platform that refugees already use to provide information in many languages to the entire community at once. Agencies could share information on in-person workshops and trainings on topics such as home buying, tax preparation, and job searches. They could also develop and share instructional videos in multiple languages, including videos on how to re-apply for Medicaid, how the health insurance exchange works, and what to do about unexpected medical bills.

On such a platform, reminders and information could be shared at just the right time, around, for example, the tax-preparation season and health-care open-enrollment period. Content on Facebook groups is also searchable for future reference, serving as an on-demand resource. Such a platform would also help resettlement agency staff respond to questions and issues raised by refugees themselves. The concerns of refugees could help inspire new communications and programs in response. Such a platform could also celebrate refugee success stories—the family that buys their first home, the woman who lands her dream job—allowing refugees to share tips and inspire one another. Refugees could be informed of key updates to the page and key events by an SMS blast, rather than by email.

6. Undertake larger studies around refugee health care and housing in the US.

While resettlement agencies can do some work to help refugees understand Medicaid and their other healthcare options, the reality is that healthcare in the US is generally confusing and expensive. But this is an issue where state or national-level advocacy might expand refugee options. In order to make the case for a policy change, a larger study of this issue is likely needed. A larger study might help explain how refugees more broadly are navigating the transition from Medicaid. What healthcare choices are they making? How does this vary by state, income level, health status, and employer-based healthcare options?

Housing is another important area for further research. Knowing more about the average share of income going to housing would be helpful, as well as how this changes over time and in different cities across the US. What successful strategies are refugees using to transition towards home ownership? Many refugees worry about what will happen if they get sick and are unable to make a rent or mortgage payment. Might there be an opportunity to introduce a savings or group insurance fund to ease these fears?

Conclusions

This small study of refugee financial transitions in Dallas showed that after two to three years in the US, many refugees are not yet where they would like to be in economic terms. While finding their financial feet has taken longer than many hoped, refugees’ history of saving, networks for mutual support, and courage to take risks and ask questions is helping them move along an upward trajectory. Healthcare expenses are a major risk to that upward momentum. While that big problem has no easy fixes, resettlement agencies and community partners have many options to better communicate with and support refugees with some of the longer-term financial tasks they face as they build new, hopeful lives in the United States.

Footnotes

References

Baulch, Bob, and Peter Davis. “Poverty Dynamics and Life Trajectories in Rural Bangladesh.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 2, no. 2 (2008): 176–190.

Clemens, Michael, Cindy Huang, Jimmy Graham, and Kate Gough. “Migration Is What You Make It: Seven Policy Decisions that Turned Challenges into Opportunities.” CGD Notes. Center for Global Development. Accessed December 13, 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/migration-what-you-make-it-seven-policy-decisions-turned-challenges-opportunities.

Evans, William N., and Daniel Fitzgerald. “The Economic and Social Outcomes of Refugees in the United States: Evidence from the ACS.” Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2017.

Refugee Processing Center, US Department of State. “Refugee Processing Center FY Data.” Refugee Processing Center. Accessed October 25, 2018. http://www.wrapsnet.org/archives/

Appendix A

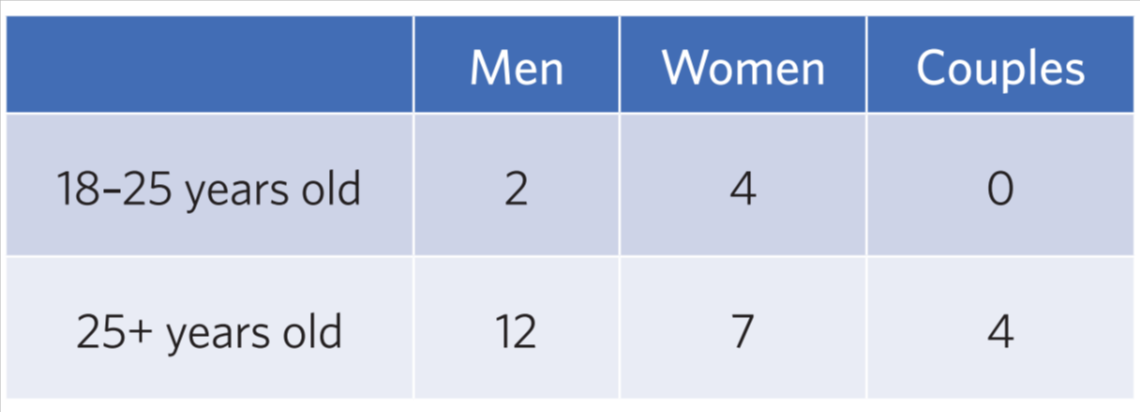

Refugee populations are very heterogeneous. Individuals come from many countries of origin, have widely variable educational backgrounds, different levels of assets upon arrival in the United States, and diverse kinds of family social support to draw on (or obligations to fulfil), both in their countries of origin and the United States. Our small study could not accommodate all of that diversity; keeping in mind the kinds of people that we were able to interview is important.

Overwhelmingly, our respondents were from Afghanistan (14) and Iraq (12) with a small number from Congo (2) and Syria (1). Many (15 of 29) came to the United States on Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs), being given the opportunity to resettle because of the risks posed to them by working with the United States government in their home countries.

For those coming on SIVs, at least one family member tended to be highly educated and have some working knowledge of English prior to their arrival in the United States.

Table 3: Respondent sample by gender and age.

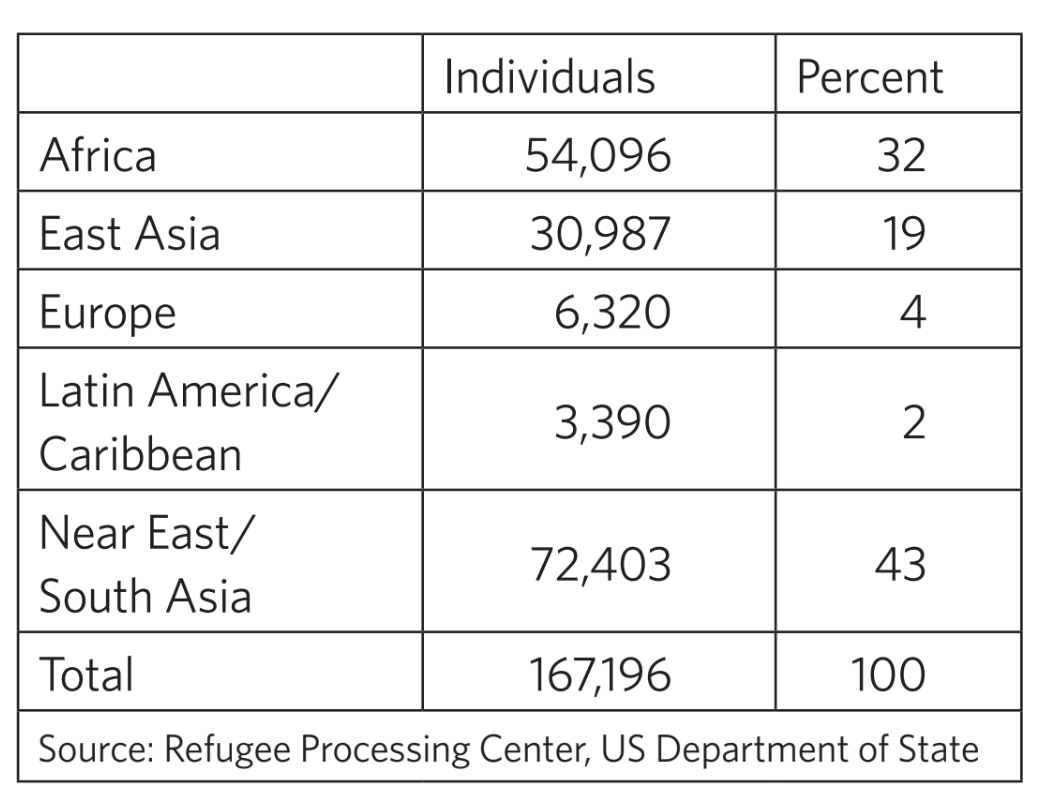

This study is not meant to be representative of any resettled group. To put our sample in context, Table 4 shows aggregated data on refugee arrivals in the United States by region in fiscal years 2015 and 2016. In 2016, SIVs represented about 14 percent of all refugees resettled, which shows that this may be a unique group, but one of a substantial size.5

Table 4: Individual refugee arrivals in the United States by region of origin, FY2015 and FY2016.

The IRC office in Dallas resettles refugees from many countries of origin, and our sample was in part constrained by our team’s language capacities. We conducted interviews in English, Farsi, Dari, Arabic, and French. Working in partnership with the IRC, we obtained a list of refugees resettled in 2015 and 2016 speaking any of these languages. Both IRC staff and our team contacted these potential respondents by phone to determine whether they still lived in the area and might be interested in participating in the study. For those who were interested, we made appointments to meet them either at their homes or a convenient meeting point, such as a coffee shop or bookstore, where we explained the study further and obtained consent to continue.

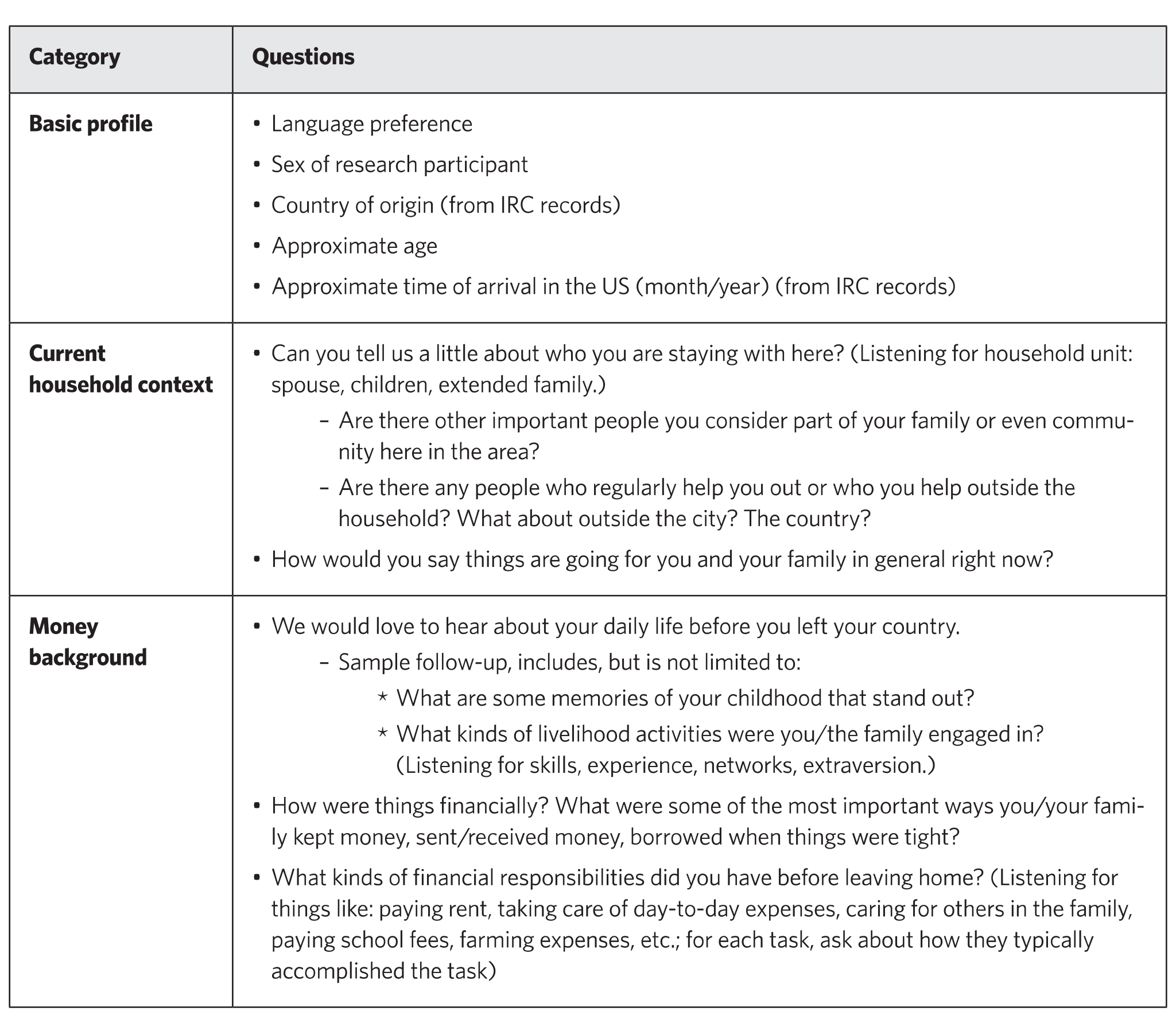

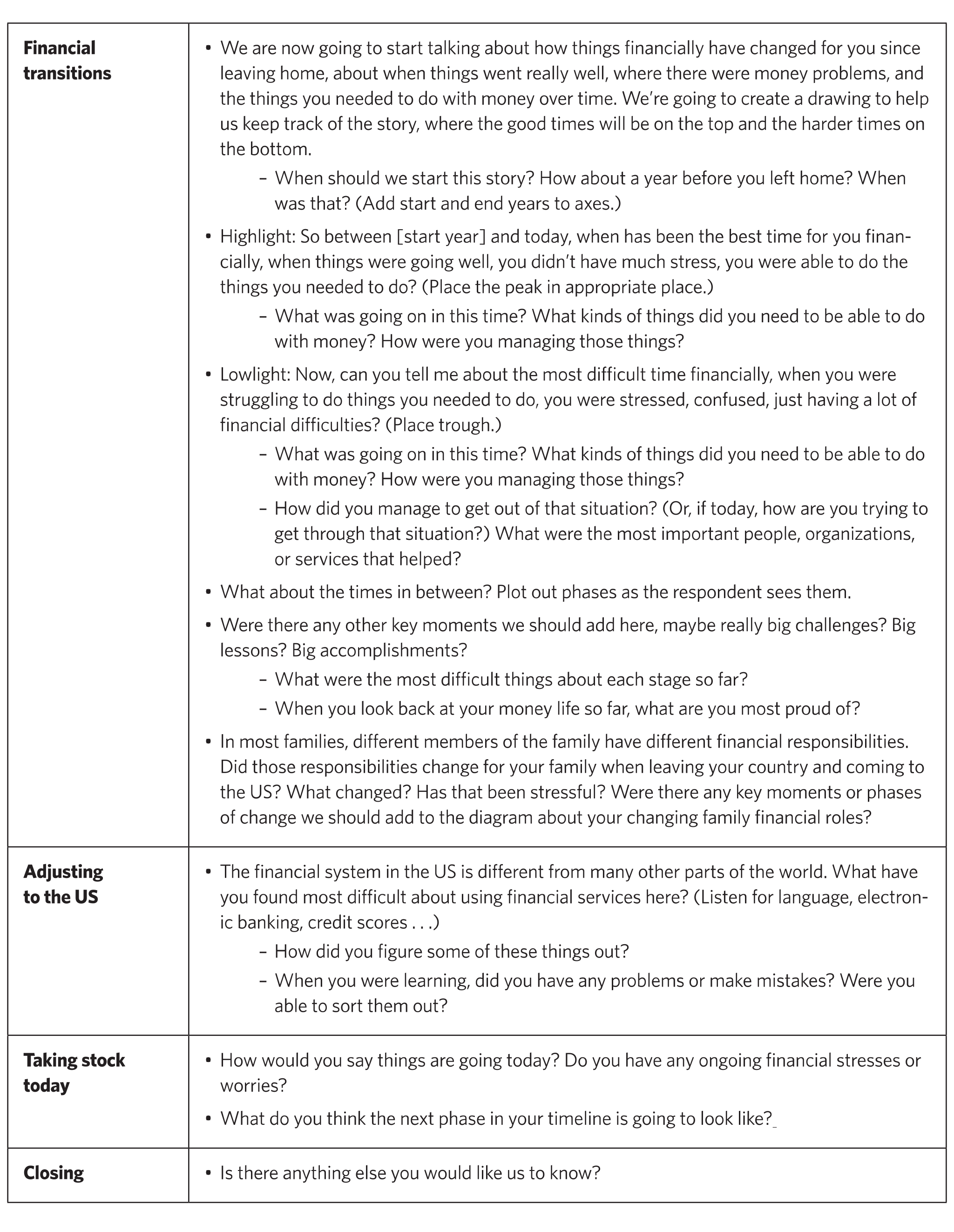

Interviews lasted between one and two hours and were conversational in tone, built around the “financial life history” narrated by the respondent him-or-herself. We worked with respondents to draw their financial trajectories on poster paper and filled in key events with narrative details.6 The discussion guide is provided in Appendix B.

Interviewers wrote detailed notes throughout the interviews, and those notes were later completed alongside interviewer's observations within 48 hours of each interview. All notes were anonymized before being read into NVivo software for qualitative analysis.

Appendix B: Discussion Guide

📝 This article was originally published as a report by the Henry J. Leir Institute at The Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy and Tufts University.

Download the original report below ⬇️

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.