Venezuelan parents utilize savings groups and balance multiple jobs in order to create opportunities for their children.

Astrid and her husband Carlos left Venezuela after learning that Astrid was pregnant with their fourth child. Seemingly overnight, the family went from vacationing at the beach to selling caramels in the streets of Medellín. Dedicated and relentless, however, Astrid and Carlos hustled to build a new life in Colombia—one that would offer their children enriching educational opportunities and secure the family’s physical and financial health.

“We used to take the children to the beach every weekend,” Astrid recalled with a hint of nostalgia. “We had a house, a car, and a full spread of groceries weekly. My husband’s work as a mechanic provided everything we needed to live comfortably.” In Venezuela, Astrid sold cosmetics and cared for her three children—“all boys,” she lamented jokingly—until the deteriorating economic situation and some unexpected news impelled the family to relocate. When Astrid discovered she was pregnant with her fourth child, Carlos decided that, given the gravity of Venezuela’s economic crisis, it was time to sell their physical assets—a car, television, and refrigerator—and move the family to Colombia.

Astrid and Carlos tried to save up funds three times before Carlos was finally able to purchase passage for himself, thwarted each previous time by more pressing financial emergencies. “We were apart for seven months,” Astrid said somberly. “We had never been separated so long—not since we met fifteen years ago.” After settling in Medellín, Carlos began selling caramels in the street and skipping meals in order to send Astrid enough money for bus fare to Colombia as quickly as possible. It took seven months, but once Astrid had enough to purchase three bus seats, she risked making the trip, which required her to convince consecutive bus drivers to let her carry one child on her lap; she didn’t have enough to pay for all four seats, she said.

When the family reunited in Medellín, they joined Carlos in a small room that he rented for $2 USD daily. Despite the higher aggregate monthly cost of renting on a daily basis ($59 USD), Carlos had been living day-to-day since arriving in Medellín and, with the majority of his daily earnings sent to finance the journey of Astrid and the children, he could not afford the lump sum of a monthly rent. After the landlord informed the family that children were not permitted in the room, however, the family scrambled to rent a one-room house up in the hills. Astrid and Carlos were suspicious of the legality of being evicted for having young children, but absent a legal residency permit (PPT), the family did not feel like they had the legal protections to fight the eviction.

Shortly after they moved to their new house, where rent was $39 USD monthly, plus $8 USD in utilities, Astrid’s fourth child was born. A few months later, she joined her husband selling caramels, carrying her child with her throughout the day while the other children stayed at the house. “It was a risk,” Astrid sighed, “but we did not have the financial stability to do anything else.” Selling in the street, Astrid and Carlos earned a collective $10 USD daily, with the occasional good Samaritan gifting them groceries or an extra $12 USD, which they would immediately save to make rent.

Recalling this period, Astrid began to tear up as she recounted the daily sexism and xenophobia she faced. “People assumed that I was a prostitute, asking me how much I charge, or touching my hand when they gave me money [for a caramel]. But as a woman, you can imagine that I’ve gotten used to dealing with that.” Astrid also faced threats from Colombia’s welfare agency that told her that her baby would be confiscated if she continued to bring him to sell in the streets. “I didn’t know that they would think I was using the baby to make more money. If I’d really wanted to use my kids to gain the sympathy of strangers, I wouldn’t have just brought one; I would have brought all four!”

After seven months of street sales, Carlos finally convinced Astrid to give it up. To compensate for the loss of income, Carlos began to work twelve to fourteen-hour days in any job that he could find—street sweeping, unloading cargo trucks, recycling, and salvaging in a junk yard. “Here in Colombia, my husband has had to do everything to earn money, including menial jobs like sweeping. He is used to a single, dignified job: working as a mechanic. It’s not that he’s too good for the other jobs, but it’s been hard to work in something he is not accustomed to like sweeping the street…. My husband would come home crying and just say that he was doing it for the kids.”

Carlos leveraged one of his jobs at the junkyard to acquire physical assets for the family’s home. He bought a discarded refrigerator, gas stove, and television that he repaired himself. Astrid, in the meantime, started cleaning houses and working at a local church on the weekends. She also went about ensuring that the entire family applied for PPT, which she knew was essential for the future success of her family in Colombia. Eventually, one of Carlos’ jobs—unloading cargo trucks for the soda company Postobón—turned into more regular employment, which lent the family greater financial stability. The consistency reduced the stress on Carlos, who had been experiencing health problems. “Low blood sugar and too much stress, the doctor told us. So now on Sundays he rests. I don’t let him work.”

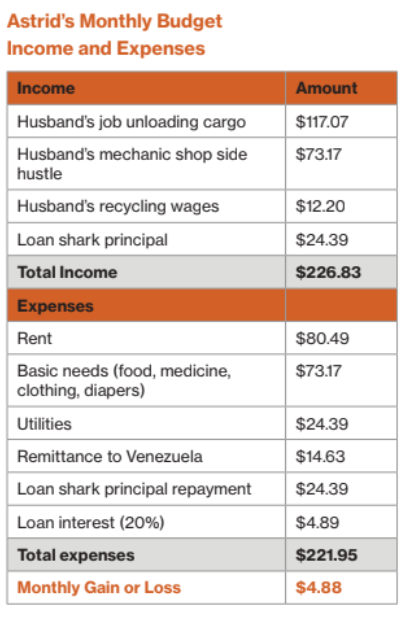

In December 2021, Astrid and her family moved to a new, three-room house, where they pay $80 USD monthly, plus $24 USD in utilities. “I was so happy to finally move to a bigger house,” Astrid beamed. “Imagine, six of us living in that one-bedroom house…. It was uncomfortable to say the least.”

Now, Carlos works for Postobón four days a week. Astrid and Carlos decided that it was preferable for him to receive a lump sum payment of $29 USD each week, rather than be paid $7 USD daily. With a lump sum, Astrid explained, the family can purchase groceries for the week and benefit from economies of bulk, rather than purchasing more expensive small amounts of food each day. Additionally, Carlos runs an informal mechanic shop out of their house, where he fixes bicycles and motorcycles. On occasion, he gets work at the recycling center in their neighborhood, which serves to diversify the family’s sources of income.

Astrid’s top priority, she said, is her children’s well-being and ensuring that they have access to educational opportunities. All of Astrid’s children are enrolled in school and numerous after-school activities such as audio-visual media classes, soccer, and English courses. By diligently managing her family’s PPT process, Astrid hopes their documentation will arrive in time for her oldest son to apply to university in the coming year. Moreover, PPT will allow her to enroll the family in Colombia’s national healthcare system and facilitate her husband obtaining full-time, legal employment from his boss at Postobón, who has promised to bring him on once the paperwork arrives.

There are still times, however, when Astrid’s family must negotiate with the landlord for flexibility in rent payments. Unanticipated costs can quickly destabilize the family’s finances, like when Astrid’s middle child had appendicitis last year. Carlos and Astrid are weary of high interest paga diario loans. “We try not to ask for any money because it can become a vice. Those daily costs of paying it back—it’s tiring,” Astrid insisted. Instead, every Saturday, she participates in a savings group composed primarily of Venezuelan women from her neighborhood, many of whom she now considers friends and often chats with via WhatsApp. Each participant places whatever amount they want into a wooden box with three locks. Keys are distributed amongst the women, but if anyone wants to retrieve their funds, all women must be present. Astrid said that the group keeps meticulous records of the deposits and that over the past month it has helped her family save $12 USD.

“Life is very different now from when we used to vacation at the beach,” Astrid reflected. “My house in Venezuela is still there, but it was robbed and has deteriorated. If I go back to Venezuela, I will have to start from zero again, the same way that I had to start from zero here. But of course, I wouldn’t have to pay rent.” Still, Astrid and her family do not consider returning to Venezuela. In Colombia, despite the adjustment, Astrid knows that her children will have better opportunities.