As times get difficult, life partners transition to business partners through their small business.

Uzair and Fatima began their life humbly enough in a part of Ethiopia that was once Somalia. Early into their marriage, Uzair rented a wheelbarrow and was able to earn income from his porter work, which had him fetching and hauling all manner of goods, from construction materials to retail goods. While living in an Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA) supported refugee community in Kebri Beyah, Fatima soon got the idea to sell snacks in the schoolyard. She pressed Uzair to help her shop for the best wholesale ingredients. Their business grew slowly and steadily, as both realized how satisfying the process had been.

“We met in Hart Sheik. I worked as a maid for an Ethiopian family,” Fatima began. “[Uzair] used to come to their house to borrow a wheelbarrow. We were both young and belonged to the same clan, so the family introduced us,” she said as she entered the tiny prayer room in a separated hut in their compound. Fatima, a middle-aged woman, was filled with pride and excitement to share the story of her business.

“It was 1991,” she continued. “My mother and I had to urgently flee Somalia due to the war. In our time in Hart Sheik [a city in the present-day Somali region of Ethiopia], we were confined to our home because we were kids. I used to spend most of my time with my mother. My father used to work with a wheelbarrow, and he would earn around 10–20 ETB per day ($0.35–0.70). Nothing more.

“When you live a comfortable life, you can go to school, but that was not the case with us,” she said with a stern voice. “I used to stay at home and help my mother by washing dishes and clothes. As I grew up, I also started working as a maid. It was mostly freelancing, nothing regular. For instance, I would go to a neighbor and wash dishes for them. I would get 20 ETB per day ($0.70).”

“My father died in Kebri Beyah.” Fatima fell silent.

I turned to her husband, Uzair, who was listening in the corner of the tiny room. He was also middle-aged and patiently waiting for his turn to speak.

“I came from Mogadishu in Somalia. When the destruction started in our country, we quickly escaped and came to Ethiopia and landed in a camp at Hart Sheik. There were a lot of refugees there back then. In 2004, however, most of the Northern Somali refugees returned home, as peace prevailed in their region. But the people who were like me [from Southern Somalia] were sent here [Kebri Beyah].

“We married in Hart Sheik, and we had to move here,” he said with a smile as Fatima blushed. “There was an established camp here. There were a lot of people. There were people from three camps who were mixed here. Our clan has always been a minority, something which made us feel different.

“Our clan is a minority in Somalia as well. We have always been farmers. We used to have our own farm where we grew cereals and maize. We used to harvest around ten sacks of maize each season. I was a kid at the time and lived with my parents. I had six siblings, but I moved to Ethiopia with my mother and sister. We got separated from my father while we were running,” Uzair paused. “My father fled with my siblings into deeper Somalia and finally found one another. Before we were transferred to this camp, my mother died in Hart Sheik. After her death, my sister was my responsibility. She was very young. She had to be piggy-backed all the time. I was a kid too and did not have any skills. My circumstances forced me to go to the market, to use a wheelbarrow to earn a living.

“I then started renting a wheelbarrow daily. I had to bring it back in the evenings, pay the rent, and then I could take it again the next morning. I had to pay 2 ETB per day ($0.07) as the rent. I would earn around 10 ETB per day ($0.35). At that time, things were different. Even those 10 ETB used to sustain us.”

With an air of pride, Uzair then said, “And I started becoming mature, and when my sister came of age, I married her off. After my wedding, my wife started helping me at each step. She even started to go to market with me. I continued working as a porter, using the wheelbarrow. We used to sell things to children: samosas, yams, beesa [like bread].” Fatima was getting impatient, wanting to speak, but Uzair continued. “My first child was born in Hart Sheik, and now I have three boys.”

Fatima was staring at him, a signal that he needed to start talking about her. He continued, “To start her business, there was no loan or investment. I started the business for her. When I used to push the wheelbarrow every day, I would give her 1 kg of flour, potatoes, or chili powder, and that’s how she started.”

Fatima impatiently took over. With excitement in her voice, she said, “I have been making sweets for the children who go to school. I sell outside the ARRA school. I started my business right after I got married. It used to cost around 100 ETB ($3.49). It would be the total amount needed to make the snacks.

“Making samosas is very difficult, especially during the day. If I start right now [2 pm], I will finish by nightfall. I make around 100 samosas a day, but these 100 samosas take from morning till 2 pm. I then take them to town. Previously, I sold them in the Kebri Beyah market.” Uzair stepped out to get the sweets she made for us to taste. Fatima continued explaining, “It is made of sugar, flour, and peanuts.” I asked if I could try it. They emphatically responded, “Yes!!”

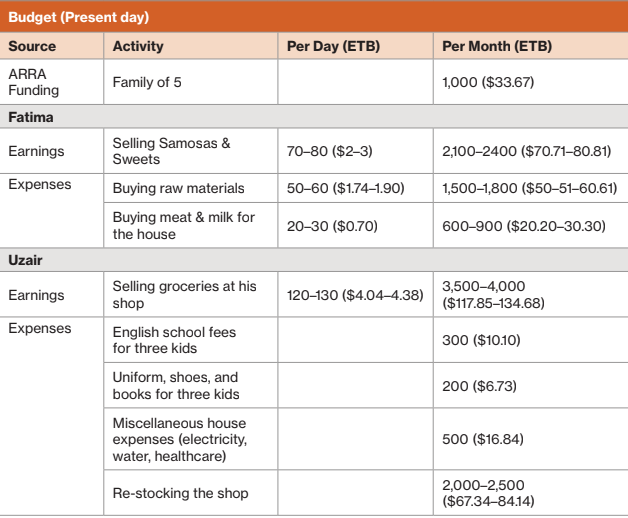

“ The profit would be 70–80 ETB ($3) per day. Before, we used to go to town together—he as a porter and me as a vendor,” she said with happiness in her voice. “I used to go to all the Kebri Beyah schools, but now I have stopped going there. I now sell everything in my shop. I then started to go to wholesalers—alone, by myself—to get potatoes to make samosas. They know me well now.”

Sample costs at wholesalers

- 1 kg onion: 40 ETB ($1.39)

- 1 kg potatoes: 30 ETB ($1.05)

- Pepper: 10 ETB ($0.35)

- 1 kg flour: 20 ETB ($0.70)

- Oil: 50 ETB ($1.74)

- Charcoal: 20 ETB ($0.70)

“The total cost for 200 samosas is around 100–120 ETB ($3.50–4.00). It would last two days. If all the samosas were sold, I would get 30 ETB ($1.05) as a daily profit.” Hearing such precise budgeting, I was curious to know more about her business model.

Fatima explained, “One samosa is sold for 1 ETB ($0.35). This is just the profit from samosas. Sweets get me the rest of my profit. However, I have stopped making samosas, as they are hard to make. I am getting old, and making them is very time-consuming. Also, samosas are always better sold in town, but I have stopped going to town. The money I make buys only the milk, meat, and soap. Beyond this profit and the ration [of money and goods we receive from ARRA], my husband provides the rest.

“I never increase my prices, as refugees would not buy the snacks. However, I don’t give any discount either.” Uzair smiled in the corner, happy to see his wife taking over the conversation.

Uzair then added, “My wife used to get 60–80 ETB ($1.05–1.40) profit from that, and I used to get at least 20 or 10 ETB per day ($0.35 or $0.07) for my porter work. I used to pay all the bills of the house. I never let my wife spend the money she earned. Instead, she would save it. At that time, around 2005, 20 ETB was more than 200 ETB ($6.97) today.

“We started running a shop using the money that we saved. We had saved around 2,000 ETB ($69.75). I went to a wholesaler in Kebri Beyah and asked him what the most important things were that I would need to open a shop. He wrote down rice, sugar, flour, sweets, gum, etc., and the total came to 2,000 ETB.

“At that time, the profit from the shop did not matter. Whatever we earned from the shop we used to put back into the business. We kept increasing the variety of things to sell. My wife stopped saving the money. After we opened the shop, she started paying the bills. She still continues to pay the bills. Whatever profit I get from the shop, I put into inventory.

“2,000 ETB ($69.75) helped us fill two sections of the shop. Things are much better now. If you try to estimate, the worth of goods in the shop today is around 20,000 ETB ($697.95). I take care of the basic needs of the kids: fees for the private school, clothes, and shoes. The rest I put back in the shop.”

Uzair explained that he never offers free products to anyone. “I just try not to take a loan and not be owed money. The wholesalers can give loans. But I am a small retailer. I buy sugar or rice or other things, but I always retail them. I will buy a sack, and then I put them in small plastics and sell them. For example, I take a carton of pasta or spaghetti. I put it in smaller boxes and retail it. That is because I don’t have a good strategic market. My economy would improve if I had more customers with more money. Then my market would increase.

“I take out around 500 ETB ($17.44) per month for my kids. My kids go to the ARRA school, which is free, but they also go to a private school for English. We have to pay for that. It is in town. It is 100 ETB ($3.49) per child per month, so it will be 300 ETB ($10.46) for three children per month.

“My wife manages most of the bills of the family, like milk and meat. If it goes overboard, I cover it up.” Uzair and Fatima glanced at each other again, this time with a big smile.

“We have a family of five, so we get 200 ETB per person per month ($6.97) from ARRA—hence, a total of 1,000 ETB ($34.87). My wife always takes the ration [of goods we receive] from ARRA, but still has to go to the wholesaler to buy a half-sack of sugar and flour.”

Turning to a discussion about their wider finances, Fatima added, “However, we have no major savings, no emergency funds. By God’s grace, my life is always normal. Life is good when you have health, safety, and security.”

Uzair recalled the time he was offered the opportunity to go to the United States. “Frankly, the best day was when I was told that I am selected for resettlement. However, I was one of the many whose process was canceled. We were told it was canceled because the president of the US has restricted the number of refugees who could come. Since that day, we are living here. We do not have any problem and we are content and satisfied with what we have.

“My oldest child is seventeen years old and is a student. I plan to send my kids abroad, if we get a chance, for their higher education. Even if we stay in Ethiopia, I want him to receive good higher education and get a job. He is currently in grade eight. I will try to send him to a university,” Uzair said with a hopeful voice.

He does, however, express some concerns and difficulties. “No one here trusts refugees,” Uzair said, sounding disappointed. “We are worse off because even our neighbors don’t trust us. They are from a different clan. The wholesalers don’t trust us, and they never give us any loans. They say that refugees cannot be trusted because they move from one place to another. But the locals are trusted, as they have land. You have to cut your shirt and your sleeves according to your status. You have to spend according to your earnings. When there is less money, you have to buy less. That’s how it works.”

Fatima jumped into the conversation, adding, “The ration from ARRA is inconsistent, too. Five years ago, we were given soap, salt, sugar, and millet. It changes every year. We are not given any soap, salt, or sugar now. They have started giving us porridge, oil, and beans. However, even the porridge is occasional. Along with the money that we are paid right now, it is always oil and beans.

“People who live in the refugee camps go to the wholesalers to buy things. If I had some more money, I would buy and sell in wholesale within the refugee camp itself.

“I tried to get [a microloan] several times. A lot of agents came to me before—Europeans and Americans. I told them that if I could get some money, I can do better. They said they will help me, but I never heard back from them.”

Fatima then reflected on her life and said, “The most valuable lesson I have learned is that I used to be a girl living with my family, but now I am a responsible wife.” She laughed. “Now I have a lot of burdens, a lot of responsibilities. I used to be a girl who used to live with my parents. Now I gave birth to children, took care of the house, and also ran a business.”

Speaking of her marriage, she added, “We command each other. Sometimes he tells me what to do, sometimes I tell him. And we have to listen to each other.” Uzair nodded in agreement.

“I would like to go to a better place. A place better than this,” Fatima said. “The humanitarian organizations always come to interview us, but I wish they would take us to the US where my mother is. I would like to see my business growing, but the most important thing is if they can take me to my mother.

“You are the 80th person who has interviewed me, so I would like the humanitarian organizations to take me to my mother. All of them [the humanitarians] were white, and I cannot separate one from the other.”