Light at the end of the tunnel seems elusive for a blended family struggling to stretch their income.

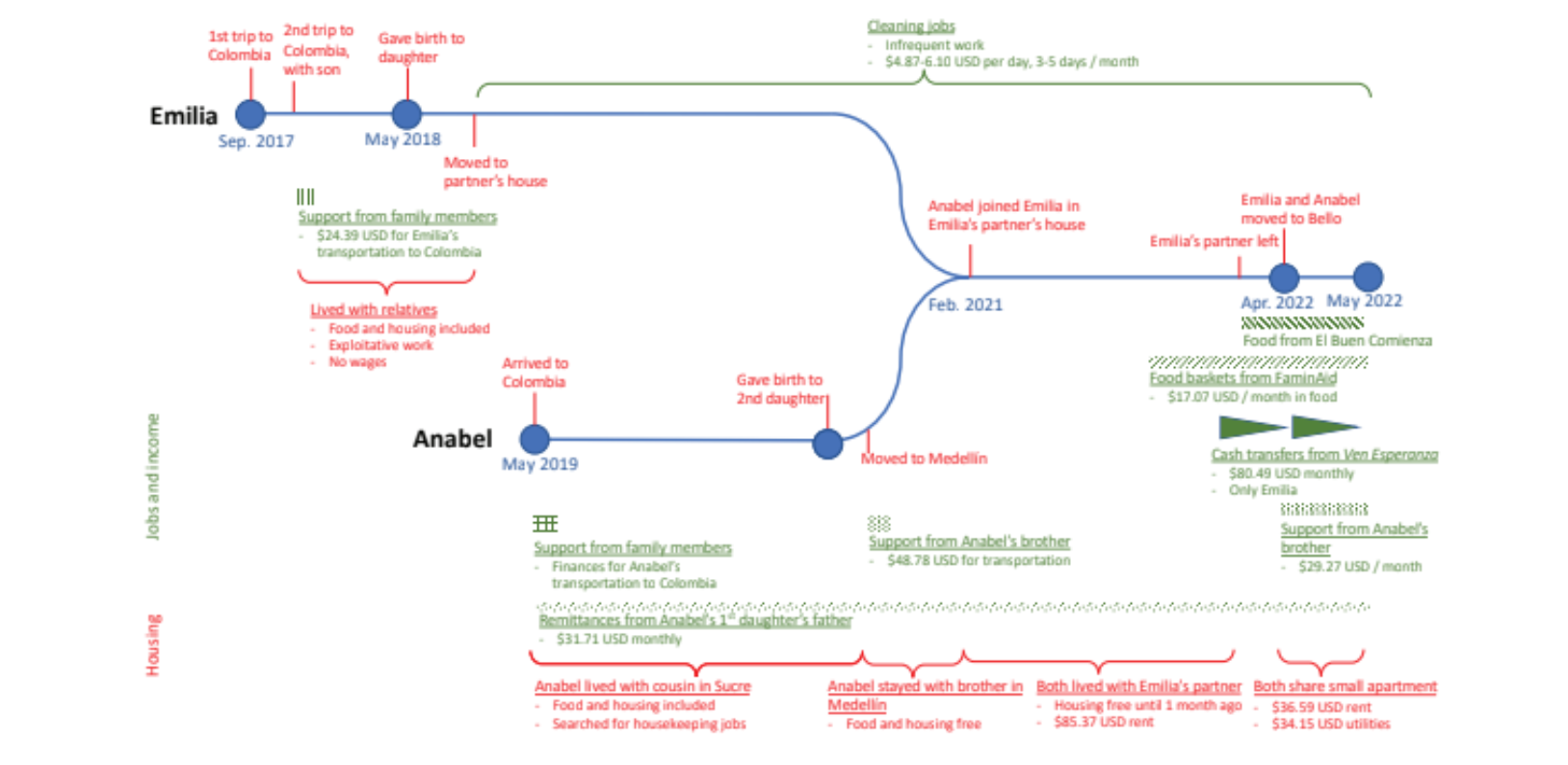

Emilia and her adult daughter, Anabel, each have two young children. As single mothers in a foreign country, they face limited opportunities but manage to survive by combining forces. Their blended household has extremely low income. Neither of them has a stable job or sufficient prospects for side hustles. To support themselves and their four dependents, they depend on support from other family members and neighbors, periodic child support payments, cash and food support from humanitarian organizations, and state-subsidized health care for a chronically ill daughter.

Despite support from family members already in Colombia, their household is stuck in perpetual state of financial precarity.

Emilia came to our interview with her adult daughter, Anabel. They both wear the same tired smiles on their faces, strongly resembling each other, as they tell their individual stories about their separate journeys to Colombia. Anabel’s fierce convictions and persistence in turning down any loans set her apart from her mother, Emilia, who seemed exhausted by the weight of supporting her family for many years and the illness of her youngest child. Long before leaving Venezuela, Emilia was the sole breadwinner for herself and her six children.

Emilia’s Journey

In 2017, as the Venezuelan economy crumbled around her, Emilia was struggling to stretch her income from house-cleaning to feed and provide for her adult children and ten-year-old son, Daniel, in the one-bedroom, one-bathroom house she owned. The 40-year-old mother reached out to family members already living in Colombia to finance a short exploratory trip without her children. She found help from a niece in Medellín, who accompanied her and paid for part of her transportation. Emilia soon returned to Venezuela to bring Daniel with her to another family member’s home in Colombia.

With only $24 USD from her family to finance her second journey, she was stuck at the border for seventeen days. To get safely to Colombia, Emilia sold a hairdryer for $5 USD, as well as candies and coffee along the route, and relied on meals from a Catholic charity.

Emilia worked for little to no pay so she and Daniel could stay in the family member’s home for free. After she became pregnant, she continued working into the advanced stages of her pregnancy. She was severely overworked, but she pressed on, believing that “those who live on the charity of others never rest.” Her daughter was born with stunted growth, requiring frequent doctor’s visits. Despite their exploitative relationship, she registered the baby in her relatives’ name, which they led her to believe was the only way to ensure access to state-subsidized healthcare and other benefits for Colombian nationals.¹

After her relatives attempted to take the child, Emilia finally left the abusive situation and moved in with her partner in a well-to-do suburb of Medellín.

Anabel’s Journey

Like her mother, 26-year-old Anabel knew she had to leave Venezuela in 2019 when she could no longer feed her two-year-old daughter. She traveled with her daughter to Sucre, Colombia, without any cash, assets, or knowledge of where she was going. Her travel was paid for by family members already living in Colombia. Her cousin took them into her home, watching Anabel’s daughter while Anabel started finding cleaning jobs.

A year later, Anabel gave birth to her second daughter. Due to policy changes in 2019, the baby automatically received Colombian citizenship. The father of her first child sent $32 USD in remittances from Venezuela every month, but now with two young children, Anabel could no longer make ends meet. Her brother, Armando, split the cost of transporting her family from Sucre—$98 USD—and housed her and her daughters temporarily in Medellín.

Seeking and Sharing Help Together

Anabel soon moved in with her mom, Emilia, in a higher-end neighborhood, where they and their four children stayed with Emilia’s partner until he left. Without his support, they could no longer afford the rent, which cost $85 USD per month. In April 2022, they had to move to Bello, a squatter settlement located in the steepest hills bordering Medellín, for less expensive housing, finding an apartment next door to Anabel’s cousin. A month later, Emilia and Anabel still owe $24 USD to the owner of their previous house, who is giving them extra time to pay it off. This debt continues to make Anabel deeply uneasy.

The same destitution that Emilia and Anabel sought to escape in Venezuela continues to define their lives in Colombia, despite living in the country for five years. They can barely afford their six-person household and small apartment, despite the low rent. They pay $37 USD per month because it doesn’t have electric outlets, and the utilities cost $34 USD per month. While Bello is an affordable place to live, it has very little economic opportunity for two women working in housekeeping and cleaning. They must travel outside of Bello, to marginally better-off neighborhoods, to find a house that can afford to hire them. Still, the opportunities are limited. They each only find work at most three to five days per month, receiving $5 USD per day of housework. Their combined monthly income from cleaning jobs is $39 USD, far below their monthly expenses for the six-person household totally approximately $207 USD.

With a household deficit of nearly $171 USD per month, Emilia and Anabel barely scrape by month-to-month, depending heavily on their social network. It is a tenuous situation, as charitable contributions from relatives and neighbors can be less consistent than income from work. Reliance on their generosity puts pressure on their relationships, and Emilia and Anabel are acutely aware that it might end at any time.

Anabel’s brother Armando pays $24 USD of the $37 USD monthly rent, and also sends Emilia an extra $5 USD every month. To reduce costs, Emilia and Anabel share food, childcare, and household items with Anabel’s cousin next door, who has four children and a husband with a relatively well-paying construction job. That cousin’s husband often gifts extra items to Emilia and Anabel’s household. Their sympathetic landlord also helps them out with food from time to time, giving them approximately $17 USD in food every week. Emilia and Anabel cannot buy food from any shop owners on credit. In Anabel’s words, this is because they are neither Colombian nor well-known to the shop owners.

In addition to their private networks, Emilia and Anabel access cash and food support through humanitarian organizations. Emilia successfully signed up for a cash assistance program from Mercy Corps two months ago, receiving approximately $80 USD every month. She has to walk one hour each way to withdraw it, but it helps pay their rent and food costs. Anabel also applied for the cash transfers and was told she would start receiving them, but she never heard back. An organization called El Buen Comienzo provides food for their daughters. Four months ago, Emilia also signed up for at FaminAid to receive a food basket every month, which she values at around $17 USD in food. Anabel has not signed up, because she is unsure whether she wants to stay in Colombia.

Prospects for the Future

If Anabel could afford it, she would set up a small business selling fast-food from a cart in the streets, allowing her to make an independent living in Colombia. To do so, she would need a deep fryer and heating container, but with her family’s insurmountable household deficit, they are far from being able to build up the savings to invest in these assets. Anabel strictly refuses to take out loans, knowing she and Emilia have no income to pay off debt if the ventures don’t pay off immediately or an emergency took priority.

For months, Anabel has been debating whether to move back to Venezuela to be closer to her other siblings and extended family. She sees no prospects for their lives in Colombia, as they have been unable to find viable livelihoods. She applied but has not yet received the PPT residency cards for herself or her first daughter, so they don’t have access to state-subsidized healthcare, free education, or other public services in Colombia. If they were back in Venezuela, she reckons, she and her daughters would have a large family network with none of the stigma or discrimination of being foreigners.

Still, if Anabel leaves, it would be even more difficult for Emilia to afford the full costs of housing. With the price of tickets to Venezuela currently too expensive for Anabel, this critical decision point has been put on hold for now.

Emilia and Anabel each came to Colombia to create a better life for their young children, but their experience of poverty and hardships has only continued in the new country. Now, Anabel must choose between the limited opportunities and continued economic crisis in Venezuela, and the isolation, xenophobia, and stressful balance of dependence on others that she and Emilia endure, with no end in sight, in Colombia.

¹ Until 2019, only children born with at least one Colombian parent receive Colombian nationality. Emilia may not have been able to register the child with the father’s name, though he was Colombian, or may not have had access to the correct information.