An adventurous Honduran man rides La Bestia in search of a better future.

Alexander first arrived in the southern state of Yucatan, Mexico, to reunite with his Mexican-Honduran girlfriend. After the relationship ended, he decided to head further north to Tijuana, aboard La Bestia, searching for better employment opportunities. He now straddles a life between Tijuana and his Honduran hometown, picking up jobs as they come and hawking merchandise when he can.

I met Alexander through another Honduran participant. The two migrants are friends and traveled together to Mexico. For our interview, Alexander and I sat on the couch of a café, with a strong fan blowing at us on a hot summer day. He seemed meek at first, but quickly shed his shy appearance to unveil a man who thrives on adventure, always seeking the next big thrill.

I am from Honduras and I have lived in Tijuana for one year and four months. Growing up, I wanted to be a professional at a company or work in electrical engineering. But in Honduras, these goals are difficult to achieve. I graduated with a technical degree in computer science after going to school for seven years in the evenings and working all seven years during the mornings. I took jobs in construction, welding, painting, or whatever would come along. Sometimes I didn’t even have a chance to shower between my job and school. I would wake up at 5:00 am to go to work and get home at midnight after school to do my homework. I used to make anywhere between 150 and 120 HNL ($6.17 and $4.94) when employers took advantage of me. They knew I needed the money, so they would pay what they pleased. After I graduated, I wanted to continue studying, but I couldn’t. I had responsibilities at home, helping my mom. I had even registered to study in a larger city and passed the enrollment test, but finances prohibited me from going back to school. Instead, I began to work in auto part sales. I was there for two years, making 4,500 HNL ($185.07) a month. That was still very little for someone with a technical degree. I should have been making 8,000 HNL ($329.02) at a minimum, but it was something. At the time, I still lived with my mother and my brother, who was in school.

I was 23 when I first came to Mexico. My girlfriend at the time lived in Mexico. Her family was from Honduras, so she traveled to Honduras often, and that’s where I met her. So, I decided to take on the adventure of coming here. She lived in Merida, Yucatan. I lived there for nine months with no proper documentation, and every employer would ask me for a work permit. I was offered 400 or 500 MEX ($19.87 or $24.84) a week to work in a cybercafe from 8:00 am to 8:00 pm. It was exploitation, so I only worked there for two and a half months. My girlfriend really helped me during that time. One day, a man came to weld the gate at the place where we lived. I asked him for a job, and he accepted me. He paid me 800–900 MEX ($39.74–$44.71) a week. I worked with him for four months and was promoted to master welder because of my hard work and dedication. He increased my salary to 1,400 MEX ($69.55) a week and covered my food.

I then started having problems at home with my girlfriend. I was a very proud young man, so I didn’t like being reproached by my partner. A friend was making his way up to the US at the time, so I took advantage of the opportunity and decided to head to the US. I was selfish in my decision, but I also had to take care of myself and my family. That was the first time I rode La Bestia.

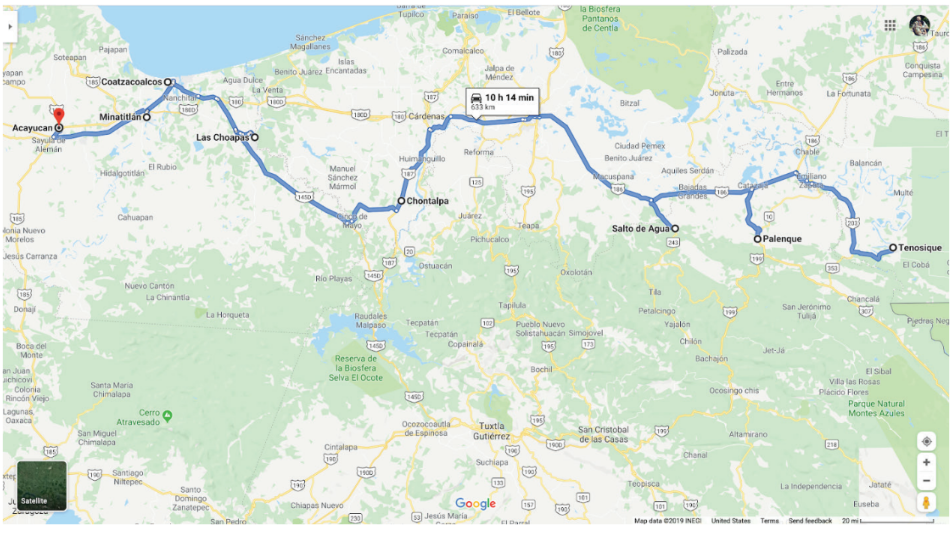

I got on the train in Salto de Agua, Chiapas. Catching the train there is a little less dangerous, but most people get on in Tenosique, Tabasco, where it’s more dangerous. Between Tenosique and Salto de Agua, the train rides through Palenque, Chiapas, where criminals hop on to mug or extort you. There, the train rides really fast. In Salto de Agua, the train goes more slowly, or sometimes even stops. There is also a really great migrant shelter there.

I had never ridden a train before. The first time I saw it and heard it coming, I felt nervous, but I also felt an adrenaline rush. I got on the train without any problems at 5:00 pm, and the train didn’t stop to rest until 3:00 am. That night it rained, and we all got wet. There were a lot of people, but not many children. In fact—though I did not witness this—on the way from Palenque to Salto de Agua, some criminals got on the train and threw a child off it. I did see the child’s mother crying inconsolably by the time I got on. That was really awful. We were risking everything on our journey.

When we arrived in Chontalpa, Tabasco, we were mugged. I think the train is allied with the criminals because it stopped at the town center but then reversed into a dark, lonely place. That’s where the criminals got on. I recognized they were criminals right away because they weren’t dirty. They were well dressed, had nice shoes and good backpacks. I noticed one of the criminals was Central American, either Honduran or Salvadoran. There was a young man with us who had hidden his cellphone in his private parts. The criminals stripped him, and when they found the phone, they beat him for lying to them. Another migrant looked at the Central American criminal and asked, “Don’t you remember me? I’m from San Pedro Sula, just like you.” The criminal looked back and answered, “Yes, I remember you. So what? I don’t care if you are my brother, my mother, or my father. I am the one in charge here. If you don’t pay, you get to stay here.” He pointed his gun at the migrant’s stomach and the migrant fell silent. The criminal then looked at me and asked, “What will you give me?” I said I had nothing, but he was free to search me. He responded, saying, “Well then, here. So you’re not off the hook for free,” and kicked me twice. They know where to kick you so you can’t get up and they can have enough time to hop off the train. Once they had hopped off, the train took off.

In Choapas, Veracruz, the train stopped again. This time, people were screaming from below, “[expletive] you will stay here. The raza [referring to angry locals] are coming to kill you.” We were scared, but luckily, they didn’t get on. At that point, we had been traveling for eight days, going hungry. There were towns where people threw bags of food to us. In other towns, the train rode by avocado, orange, and mango trees, and we would jump to reach the fruits. Yet other times, when the train stopped, some people would get off and ask locals for food. Some migrants would bring canned food with them to eat along the way. The only perishable food we took with us were cheese and tortillas. Everything else needed to be canned or it would spoil.

When you are on the train, you are under the sun. If it rains, you get wet. You can’t sleep because if you fall asleep, you risk falling off the train. You feel discouraged and sad, wanting to cry, thinking about your family and your life. You doubt yourself and ask whether what you are doing is the right thing, if it’s worth it. At the same time, you think, “I should just go back.” You also gain courage, though, and make friends. That’s the beauty of that adventure. Unless you live it, you will never know. It’s both awful and beautiful. You find people along the way who you might never see again, but you feel like you’ve known your whole life. They cheer you on, they bring you comfort, they motivate you, they share their food. When they see you are sad, they find ways to make you laugh. You feel closer to them than to friends you’ve known your whole life. You can be good, bad, a drunkard, a drug addict, a criminal, Honduran, Salvadoran, or Guatemalan… It doesn’t matter. On La Bestia, you are all one.

That first time I rode La Bestia, I didn’t get very far,” Alexander laughed. “I got to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz. Many of the migrants on board, including myself, decided to get off in Coatzacoalcos to take a bus past the most dangerous parts of Veracruz: Coatzacoalcos, Minatitlán, and Acayucan. Some people said there was an immigration checkpoint in Acayucan, but others said there wasn’t. We thought about it but decided to go anyway. We wanted to avoid Coatzacoalcos because it had become a very dangerous place. We heard cases of muggings, beatings, and migrants found chopped up by machetes.

We were on the bus, on a highway when the driver took a detour into an immigration checkpoint. The immigration officer got on the bus and came directly to the five of us who were migrants. He didn’t ask anything and only said we needed to get down because we were migrants. We were imprisoned in Acayucan for three days, almost four. After that, we were deported back to Honduras.

I stayed in Honduras for nearly three years after I was deported and worked in the craft I had learned in Mexico: welding. I had to start from scratch, but eventually, I was able to buy some clothes and tools for my business. However, it was still not a livable situation, so I decided to head back to Mexico again, on La Bestia, in 2017.

This time around, it was the same adventure, though it was more difficult. At least this time I was more mature, had more experience, and came with five friends. I decided to go to Tijuana because my older brother was living there and said he could help me and my friends. I took 23 days to get here, and my friends took 25. The difference in arrival times was because in Guadalajara, the train went through really fast, so we had to do this thing called “poncharse el tren” [take the air out of the train]. This means someone jumps on the train and finds the levers that release the air pressure from the train. This forces the train to stop, to build up air pressure once more, allowing migrants to jump on board.

My friends and I had been waiting for three days in Guadalajara. There were about 20 migrants who couldn’t get on the train due to its speed. We were in danger because we had almost been mugged three times, so we didn’t want to be there anymore. There was a young man who was known for taking the air out of trains, so we paid him about 300 MEX ($14.90) to do it, but he failed. On the fourth day, we decided someone from the group had to do it, or else we would never leave Guadalajara. Since I have always been adventurous and have played soccer for most of my life, I’m pretty athletic. So, I said I’d do it,” my face revealed the immediate worry I felt as he laughed.

I gave one of my friends my sweaters and bags, only keeping a sweater tied around my waist. The train was coming, so I began to run to match the train’s speed. After running about 300 meters (328 yards), I managed to grab on to the train, but it was going too fast and began to drag me. I don’t know how, but I managed to get on. I could hear the group cheering, “He’s on! He’s on!” Unfortunately, the train was intermodal, meaning it could not be released of its air pressure,” Alexander laughed, recounting the irony. “When the train dragged me, my sweater fell off, so all I had were the clothes on my back. I couldn’t get off because if I tried, I could kill myself. The train stopped about an hour from where I got on. I had no phone, no money, no other clothes. I thought about getting off and waiting for my friends but then realized the train was only stopping because it needed to change tracks. In any case, I got down and someone on the train asked me why I was getting off. I explained I had no money, no phone, nothing, and my friends had stayed back. He said to get back on and he would help me with whatever I needed. I got back on, and this man lent me his phone so I could call my friends and tell them what to do next.

This train took five days to get to Mexicali. I had to run away a few times because the guards forced us to get off at the terminals. I also managed to hide a few other times. On the train, I went through the desert at night, without a sweater, and felt like I was going to die. I managed to find a cart that had some holes and hid from the cold there. In the mornings, I felt chills that made my bones weak. When I finally got off the train, I fell because my body was so debilitated.

Once in Mexicali, I called my friends to let them know I would wait for them there, and I went to a cybercafe to contact a friend that lives in the US, who had offered to help me. This friend sent me money, and with that, I was able to pay for a hotel and buy some clothes while I waited for my friends to arrive. I had to ask a shoeshine to pick up the 3,000 MEX ($149.04) for me at Western Union and paid him 300 MEX ($14.90) for the favor. The money was also enough for me to pay for my friends’ hotel room once they arrived. That way, we were all able to clean up and avoid looking like filthy migrants. After that, we left on a bus to Tijuana.

Once in Tijuana, I contacted a friend who allowed us to stay with him for a week, after which we all pulled together our money to rent a room, which cost 2,300 MEX ($114.26). It was hard to get a room because no one wanted to rent us anything, simply because we were migrants who lacked proper documentation. Eventually, we came across a guy who liked us, I guess. He asked if we were Honduran and said he liked our accents. We talked to him for a while and found out his mom was renting out some apartments. With his referral, his mom gave us two weeks to come up with 1,500 MEX ($74.52) for the deposit and 2,300 MEX ($114.26) for the first month’s rent. We all found a way to come up with the money by asking for help and working in whatever jobs. And that’s how we started out.

Within two weeks of my arrival, I managed to get a job at a pozole restaurant. I had never cooked professionally but had always liked cooking. I started out as a dishwasher and eventually became a delivery man, washed corn, and did a little bit of everything for 1,200 MEX ($59.62) a week. I had to walk 50 minutes every day to work. I couldn’t continue working there for 1,200 MEX, so after eight months, I apologized to my boss and told her I wanted to find a job in my craft. She was very understanding and told me the door remained opened if I ever wanted to work there again.

Fifteen days after leaving my job at the pozole restaurant, I managed to get a humanitarian visa. I had requested a visa from immigration before, but they were reluctant to help until the arrival of the second migrant caravan. As a way to help migrants remain in the country legally, the president of Mexico offered to provide us humanitarian visas. I received my visa within 25 days of applying but had to regularly check on the status of my application at the immigration offices. This meant I had to miss four days of work to stand in line and wait for officials to confirm whether my visa was available or not. After four different instances of waiting for their response, I explained I couldn’t request any more time off work and asked whether they could notify me once my visa was ready. The official I spoke to said they didn’t offer that service and that if I wasn’t at the immigration office to pick it up when it was ready, I would lose it. I explained my situation to another agent, who seemed nicer and more reasonable, and he was able to help me. He let me know I could show up the next day before work to pick it up. Alas, the next day I received my humanitarian visa.

With my visa in hand, I decided to go back to Honduras to visit my mom. I hadn’t seen her in a year. I was with my mom for fifteen days. I also managed to get my passport while I was there. Now I am more than legal in this country. I got my passport stamped in Guatemala and Mexico and now I can access the money I’m sent.

Even though I’m legal, things are not easy in Tijuana. I don’t feel comfortable here, especially not in places frequented by people with money. There are many racist people who mistreat us, look down on us, and judge us as soon as they find out we’re Honduran. They think we’re all the same. I acknowledge that some Hondurans have come to Tijuana and messed up. They’ve been disrespectful and have done bad things. But because of one, ten are misjudged. Because of ten, one hundred are misjudged. Just like there are bad people, though, there are also good people. The racism even gets in the way of us accessing certain jobs because employers will say, “Oh, he’s Honduran? We won’t hire him.” If they do hire us, they want to pay us less, just because we are Honduran. That happens in jobs like construction or jobs at the local market. It happens less in company jobs, as long as one is documented, but sometimes employers will ask for our birth certificate, and we don’t have them. They use that excuse to deny us jobs. There are also friends of my Mexican friends who’d rather not hang out if I’m around. The police stop us randomly, pretending they’re doing checkups. Even when they don’t find anything, they detain us, just so people can see they’re doing their job. They’ll put us in the police car and drive down two streets before letting us out. All we can do is bear it, keep our heads down, and bite our tongues. When Donald Trump said Mexicans were the worst plague and discriminated against them, Mexicans were up in arms, calling him racist. Now, Mexicans are doing the same thing to Hondurans and Haitians. I think that is very hypocritical. There are some Mexicans that are good, though. I just don’t understand why some are so mean. This racism pushes me to think about leaving Tijuana.

Right now, I’m working off and on as an independent welder. I’ve also traveled to Mexico City, to Tepito [a large and dangerous market], to buy merchandise, like perfumes and lotions, so I can sell them in Honduras. Finding a permanent, more stable job here is difficult. I had some friends who were working for a company but had to leave due to bullying. People say we’ve come to steal their jobs, so sometimes we’d rather stay away from companies to avoid dealing with that. Mexicans also say they’re getting paid less because of us because we’re willing to accept less money for the same jobs. There are jobs everywhere here, though. The thing is that Mexicans just want to work in an office with air conditioning and are looking for someone to blame when they can’t accomplish that. I’ve lived and traveled to various parts of Mexico, and I have never felt the kind of racism one experiences here, in Tijuana.

My plan now is to stay here and hopefully get a job at one of the companies where they treat migrants well. Luckily, I have no vices, no kids, and no wife. My only responsibility is my mother, so I can stretch out my money well. When I send my mom money, I send it through MoneyGram or Western Union. I just don’t like Elektra because after a while of sending money, Elektra blocks you. I now have a savings account and a debit card from BanCoppel, so I can keep my money there without any problem. That way, I pay for things with my card and don’t have to carry cash around. If I get mugged, it’s not a big loss. Now that I have my passport and everything, I have access to those services. I also have a few friends who have made it to the US and will send money sometimes, just to help. I pool that money together with what I make, and I send money to my mom whenever I can.

I hear a lot of people who have made it here tell others not to come, that it’s not worth it, that it’s hard and dangerous. I can’t say that because I was told the same thing, and there are people who really need to be here. Who am I to burst their dreams? That would be selfish of me. If you think you’ll be better off here, come. Just behave. There is suffering involved, but that’s life, and you just have to move forward. If you come here, don’t go back. It’s such a waste of time and money. Don’t give up.