A single mother of nine serves as her family’s caretaker and breadwinner.

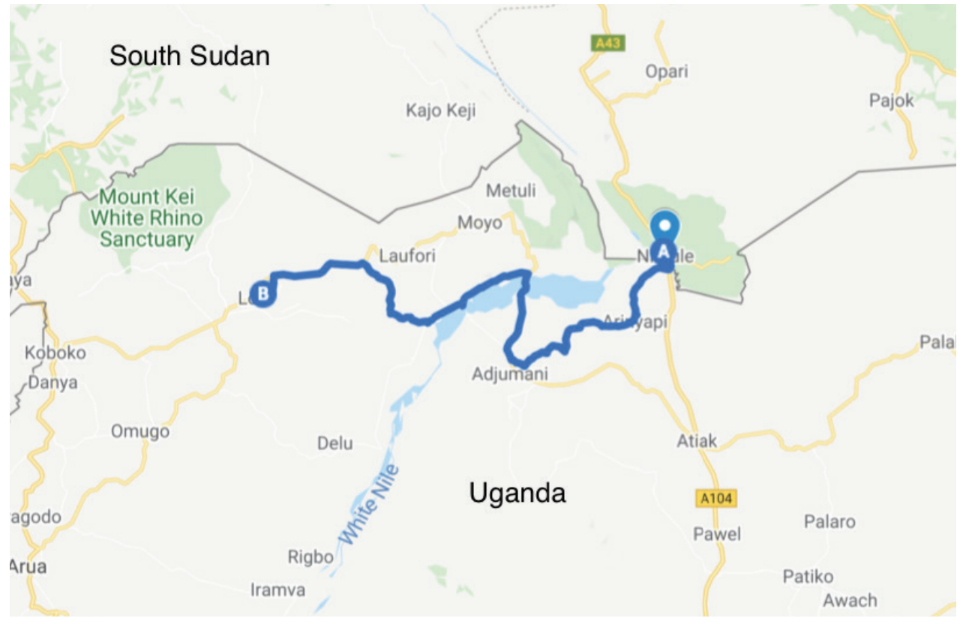

Kadi, who once ran a small but stable business in South Sudan, arrived in Uganda with few resources but abundant tenacity. As a single mother, she balances the family’s short-term expenses with long-term investments to better provide for her children.

In her cozy and crowded home in the Bidi Bidi Camp, Kadi is busy preparing the family to visit the mosque later today. She has her hands full, caring for nine children and stepchildren, but she pauses amid the hustle and bustle to share her story with us. Born a member of the Jeru tribe in South Sudan, Kadi has been living in Uganda as a refugee for the last three years.

Kadi, only thirty-five at the time of this interview, gave birth to her first child at fourteen years old, and assumed the roles of caretaker and breadwinner very early in life. A year before the war, Kadi and her husband separated because he had not paid any dowry and did not provide for his family. Instead, it was Kadi who provided for their home and family and Kadi who made a business of selling cooked food, groundnuts, and groundnut paste. Her costs were low and her business was profitable. She purchased groundnuts for 10,000 shillings ($2.70), roasted them, and then resold them for a profit at 30,000 shillings ($8.10). Kadi also sold prepared meals, bringing in roughly 150,000 shillings ($40.60) a day, double the cost of her inputs.

After the war began Kadi was forced to leave it all behind, but she brought her business acumen to the refugee camp. In this new context, Kadi began selling tomatoes and dagaa (a dried fish). “I befriended some people from the host community who showed me where I could get a tomato supply,” Kadi said.

She hoped the business would be sustainable, but as the camp’s population swelled, so did Kadi’s competition. “I was making a profit in the beginning, but the market was getting small when more people started selling the same things I was selling,” she said. Tomatoes, she added, also do not have the best shelf life. Thus, not long after its inception, Kadi chose to close down her small business.

Kadi shifted and diversified her investments. Upon entering the reception camp, Kadi used her savings to purchase five goats at 50,000 shillings ($13.50) each. After being officially admitted to Bidi Bidi Camp, Kadi exchanged her goats for a cow. Next, Kadi made an arrangement with a farmer in the host community: he watches her cow and, in return, he receives either a goat or a calf. Her cow has not yet given birth and thus has produced no new wealth. If she were to sell the cow now, she could sell it for a price of 600,000 ($163.40). However, Kadi has no plans to make such a sale and views the cow as a long-term investment. “It is the only thing that my children have,” she explained.

Having now lived at Bidi Bidi since 2016, Kadi has watched – with increasing concern – as the social and economic environment in the camp has changed over time. “When we first came, there was plenty of medicine. Nowadays, if you are diagnosed with malaria, they give you a half-dose or they don’t give you any medication. You are forced to buy,” Kadi lamented. One of her children has been diagnosed with malaria several times since they moved into Bidi Bidi. Each time he falls ill, Kadi takes him to the clinic and pays 1,000 shillings ($0.27) for the consultation, 9,000 shillings ($2.43) for injections to cure the disease, and 500 shillings ($0.13) for painkillers. When these unexpected expenses arise, Kadi sells the family’s foodstuffs to pay for the necessary medications.

Kadi considers herself lucky to have arrived in the camp with a bit of a financial buffer, having brought her savings from the business back home. But in 2017, with no regular income and the savings diminished, Kadi knew she needed to find a way to make more money. “I am frustrated because I don’t have money. I used to make money daily. I am constantly thinking of how I can get capital and start another business,” Kadi said glumly. “If I get capital, I will start selling groundnuts here in the camp and if the business grows, I will move to a nearby town,” she explained.

Luckily, Kadi tells us, there has been enough aid for the family to get by day-to-day. They receive 80 kg of maize, 15 kg of beans, and seven liters of cooking oil every month, and the children are all attending school in the camp. While the school is no-cost, Kadi had to invest 9,000 shillings ($2.40) per child for the appropriate uniform. As some of the children are still nursery-age, Kadi says any work she undertakes will need to have flexibility and proximity to her home and school.

Early in 2019, Kadi joined a farming group where the members are contracted to farm on behalf of an organization sponsored by Danish Church Aid. The group was formed recently, and each farmer has been given chia seeds to plant. Kadi was provided land by a host community member whose property had been lying fallow for years. He made it available for the refugees to use, and Kadi secured three-fourths of an acre for her chia crop. Kadi hopes to garner an income from selling chia seeds and groundnuts and hopes to see returns on her investment in the cow sooner rather than later.