A baker and businessman hopes for access to affordable credit.

Nelmar started selling cakes as a means of financing his journey from Venezuela to Colombia. Short on funds, he forged a small business out of his limited resources that allowed him to survive, save, and support his family back in Venezuela. Once in Cartagena, Nelmar’s recognition of the importance of credit became central to his growing business, and its biggest constraint. Calculation and prepared, but unable to access affordable credit, Nelmar is hopeful that his diligence will pay off when credit is finally available to all.

The moment he entered the second-floor classroom in Cartagena, Colombia, the young man’s salesman-like charisma was on full display. “Do you want me to turn this fan on,” he asked before I could say a word, “the heat here is horrible. My name is Nelmar, by the way, it’s a pleasure to meet you.” Dressed in jeans, sneakers, and a collared shirt, the 27-year old strolled across the room to shake my hand. “What do you have in the folder?” I asked, noting the ream of documents under his arm. “I brought everything I have concerning my business, but we will get to that.”

After exchanging pleasantries, Nelmar recounted his journey to Colombia. In 2018, at the age of 23, he left Venezuela owing to the deteriorating economic landscape. After graduating high school, he began working in the fields planting and harvesting crops—work that was no longer feasible, he lamented. Even government employees—teachers, police, civil servants—did not make enough to purchase basic necessities; a week’s salary only sufficed for a kilogram of cheese and a bag of flour.

Nelmar’s initial plan was to travel to Cartagena to join his sister, who had left Venezuela a year earlier, but after crossing the Venezuela-Colombia border in Maicao, he was short on funds. “The guards on the Venezuelan side charge ‘fees’ to cross based on your appearance—that is, how much they think you can pay,” he said with a dismissive laugh. “I settled in La Guajira for three months. That’s where I started to sell cakes.” Nelmar rented a small room with a basic oven for $59 USD a month and, with a $24 USD loan, purchased cake molds and ingredients to start baking—a skill he had learned from his sister at a young age. Every day, he would bake ten cakes, which he initially sold for $0.24–0.49 USD, before bumping the price to $0.73 USD, which allowed him to earn better margins from the nascent business. Each month, after paying rent and utilities, reinvesting in ingredients, and sending remittances to his family in Venezuela, Nelmar netted a profit of approximately $49 USD.

For three months in La Guajira and for nearly four years in Cartagena since, Nelmar has honed his craft, and his business model. Upon moving in with his sister in Cartagena, Nelmar realized that without residency documents (i.e., PPT), the only jobs he could obtain were exploitative and did not pay a living wage. Consequently, he decided to work for himself, securing the necessary materials and building a clientele in the neighborhoods adjacent to his house. “My sister worked in a bakery in Venezuela and taught me how to make fancier types of cakes, like tres leches, quesillos, and brownies.”

With greater variety, and a larger oven, Nelmar was able to increase both his production and his prices, but the true key to his business’ success has been credit—not credit for himself (as he is wary of high interest loans), but credit for his clients. “All of my customers have five days to pay for the cakes, because some people aren’t paid until the end of the week or every fifteen days.” This flexibility in payment options, he explained, permits customers to purchase cakes for birthdays, holidays, or events, while also giving them a handful of days to pull the money together. Prices ranging from $1.70–2.90 USD per cake, or up to $5 USD for a special decoration, meaning that repayment is not onerous for his clients, and the majority are regular customers.

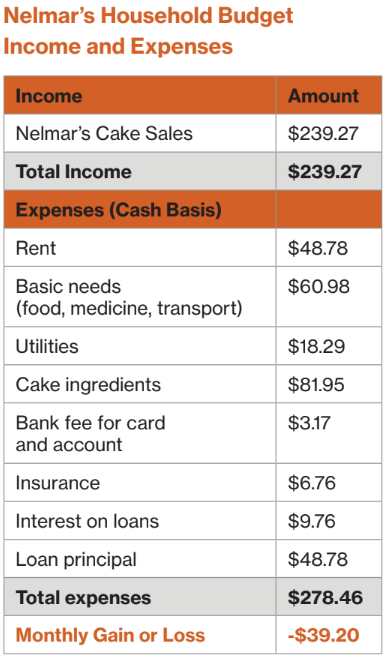

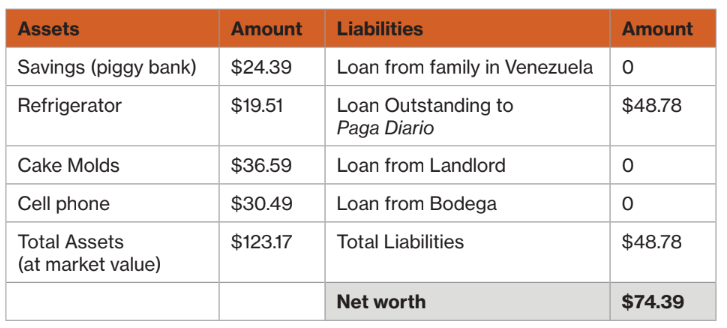

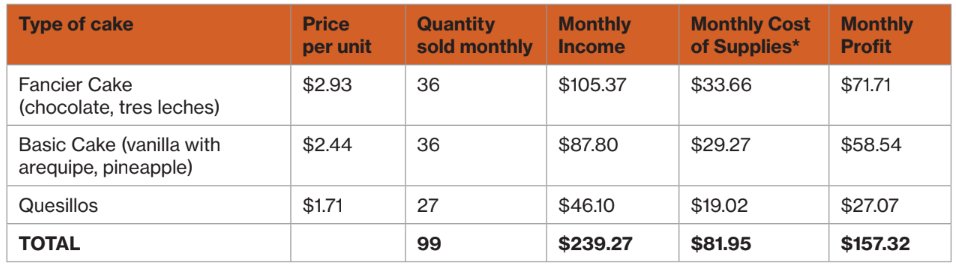

Nelmar’s insightful business model is also complemented by his precision in calculating and tracking costs. As he began to detail his business, Nelmar reached for the ream of documents, extracting hand-written calculations on the exact prices, monthly sales, and profits of each type of cake. All expenses were itemized and listed at current market prices, he explained, placing the list on the table in front of me, as he recited it from memory and occasionally paused to ensure that I was following along. “Tres leches, for instance, costs $11 USD to purchase all the ingredients—eggs, flour, milk, etc.—and I sell a dozen for $35 USD—that is, $2.90 USD each unit multiplied by 12—then, subtracting the $11 USD spent on ingredients, I end up with a profit of $23 USD, which represents a margin of 68%.”

After he had performed the same exercise with vanilla cakes and quesillos, Nelmar reached into the folder, pulled out a bright yellow bank card, and placed it on the middle of the table. As a recipient of Colombia’s Permiso por Protección Temporal (PPT), Nelmar explained, he was able to open a bank account with BanColombia, which he used to purchase supplies for his business, and track and save his earnings. Each month, he paid $3.20 USD to maintain the account, which included access to an online banking application, where his income and expenditures were broken down by category. On his phone, Nelmar then pulled up his Unique Tax Registry (Registro Único Tributario), a document that would allow him to legally register his business with the tax authorities. “I haven’t formalized the business yet,” he said, “but my goal is to grow the business to the point at which I can become official.”

When I asked Nelmar about his access to credit, he grew serious and sat still for the first time. “The bank does not offer credit to Venezuelans,” he stated dryly. As a result, he occasionally relies on usurious loans from paga diarios, or loan sharks, who charge 20 percent interest and require repayment within the month. Despite his weariness of such loans, Nelmar said that they were his only option, and that he used them sparingly. Given the temporary nature of his migration status in Colombia, Nelmar figured that the banks were worried about the credit worthiness of Venezuelans, but he maintained hope that national laws would soon change for the better. In fact, Nelmar’s use of the BanColombia card and account, he said, in addition to serving as a tool for managing his business, was a means of building credit worthiness in hopes of a change to the laws.

Extending credit to his customers is central to Nelmar’s business model, but without access to credit himself, Nelmar worries that his business is plateauing. Currently, Nelmar sells cakes along his route 23 days a week, while the other days he walks along the route to collect payments. Given the time it takes to collect payments on foot, Nelmar can only sell three weeks out of the month. He also still relies on a basic oven, he said, which limits him to baking five cakes at a time. Each batch requires one hour in the oven and, at a weekly production of 33 cakes, Nelmar spends much of his time waiting for his cakes to bake—not to mention the time he spends purchasing materials, preparing the batter (by hand), and decorating.

Efficiency is essential for Nelmar as the primary earner in his household of five, which includes his sister, her daughter, and Nelmar’s two children, ages one and four-years old. The blended family lives in a house that costs $49 USD monthly in rent, plus $24 USD in utilities. María, his sister who studied baking in Venezuela, cares for the children and occasionally sells cakes to friends in the neighborhood. When she can, María contributes $9 USD towards utilities, but the lion’s share of costs—food, diapers, clothing, medicine—are covered by Nelmar. From the baking business, Nelmar earns about $157 USD monthly, which he uses to pay rent, utilities, and purchase necessities. However, it is not enough to consistently save, as evidenced by his occasional use of paga diario loans.

Nelmar’s lack of access to credit, however, has not stopped him from planning his business’ growth. In fact, he has a clear vision of exactly what he needs to turn his nascent business into an operation that can be formalized: an oven, a mixer, a scale (in grams), and a decorating stand. By reducing the time it takes to bake cakes, Nelmar said that a proper oven could increase both his sales and production capacity. More time means that he can expand his sales routes and respond to the growing demand. Similarly, a mixer would streamline the process of making batter, as would a scale. Currently, Nelmar purchases exact quantities of his ingredients at the store, which is necessary for ensuring that each recipe receives the intended amount of each ingredient, but it also makes ingredients more expensive, because he cannot buy in bulk. The decorating stand, he said, would make it easier to do custom cakes, which have been increasing in demand. And finally, recognizing that he cannot grow the business alone, he plans to employ 2–3 people to help him collect payments and sell cakes along new routes in Cartagena.

With these four implements and a few employees, Nelmar is confident that his business will thrive. “I only need basic tools to grow the business,” Nelmar insisted. Until he can access affordable credit or receive sufficiently flexible seed capital from an NGO, however, Nelmar’s hands are tied. And yet, he doesn’t think about returning to Venezuela. “Even if the government were to change today, it would take years for the country to return to any level of prosperity,” he noted with a sigh. Instead, Nelmar’s diligent planning and accounting attest to his long-term vision for his business and his family in Colombia. His customers enjoy access to credit; Nelmar just needs it himself.