“The Phrase ‘Where One Eats, We All Eat’ is Dead”

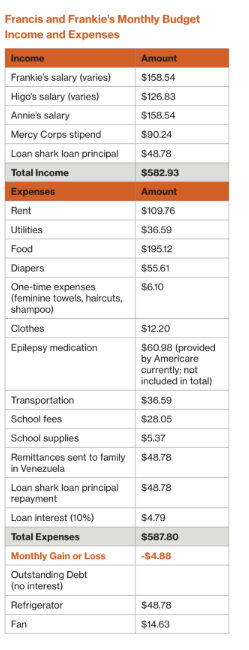

Coping with daily scarcity and the predatory interest rates of loan sharks, saving is impossible for a family trying to forge a new path.

Francis and Frankie head a large mixed family with three generations. They all came together to Colombia in 2020 in order to keep their granddaughter Jimmarys safe and healthy; her life-saving epilepsy medication had become impossible to purchase in Venezuela due to the economic collapse. In 2022, two years after first leaving, they continue to barely survive. All of the family members pool their incomes, but they also depend on debt to sustain the many costs of a household with two children and four adults. Frankie and Francis are so focused on keeping the family afloat, including some family members back in Venezuela, that they haven’t been able to plan even for the near future.

Frankie and Francis are about to celebrate their 26th anniversary together. Their personalities balance well. Frankie is a soft-spoken and stoic man, while Francis is confident and with a strong voice. They rush into the hot room a few minutes late to our scheduled interview, but once we settle down, they share their journey through three difficult years since they migrated separately, leaving their home in Venezuela to move to Cartagena, Colombia.

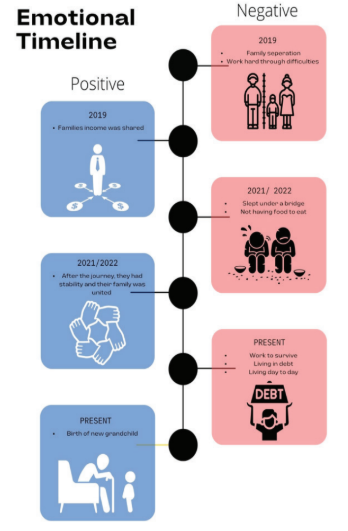

In Venezuela, Francis was a pastry chef, owning her own business at one point. Frankie worked for 22 years as a sushi chef. With their shared incomes, they lived happily with their children and grandchildren in a small three-bedroom house they owned in rural Venezuela, growing vegetables in their small patio garden.

However, in 2020, as Venezuela’s economic crisis worsened, the family could no longer find or afford the medication they needed to mitigate Jimmarys’s nightly epileptic attacks. Francis’s mother was born in Colombia and had family throughout the country, so Francis asked her aunt in Cartagena to help her find housing. Francis embarked on the journey ahead of the rest of the family, taking Jimmarys with her to secure her medication as quickly as possible. With her aunt’s help, she secured a small house with a monthly rent of $110 USD, plus utilities.

The guarantee of housing allowed Frankie, Higo, and Annie to follow one year later, now with a new grandchild. Annie had given birth to a son, Anis. After the year-long separation, a harrowing journey without food or shelter, the responsibilities of working, caring for Jimmarys alone, and finding the rental house for her family, Francis finds her happiness in being together once again. Looking back at the year before they arrived, she sees the toll it took on her mental health and her ability to imagine a hopeful future.

Frankie, Higo, and Annie began searching for informal work to cover household costs, especially food, clothing, school fees, diapers, and medications for the children. They had left Venezuela to prioritize Jimmarys’s health, and they wanted to also build a future for her and Anis. But costs continued to pile up, forcing them to live in survival mode with whatever work was immediately available. Thankfully, they began receiving Jimmarys’s medication through a humanitarian organization, saving them $61 USD every month. Still, they didn’t know many specific details about this organization, and because they were so financially dependent on the medical assistance, they lived in constant fear that they might wake up one day to the news that the assistance had stopped.

Two years after their move, the family continues to live in the same situation, with Frankie, Higo, and Annie pursuing unpredictable, informal day-to-day work. They work every day that they can, but they still cannot build up savings against their large monthly expenses. Frankie, like many, is a side hustler. He takes on multiple informal jobs like selling Fritos or coffee, looking for anything to pay the rent, but often he can’t find enough work. He can usually piece together a daily income around $6 USD. Annie works selling Fritos for a larger business, which provides a stable daily income of $6 USD. She doesn’t own her own cart but knows that she would make more each day if she didn’t have to pay the cart rental fees to the owner. So far, though, she has been unable to put aside enough savings to buy the cart. Higo’s work as a moto taxi driver adds an average income of $5 USD per day. For Frankie and Higo, not having a fixed income makes it nearly impossible to save or predict how much money they will be able to contribute to paying bills at the end of the month. Finally, Francis has taken on full-time childcare for Anis and Jimmarys, so she cannot contribute income. Her contribution is freeing up Higo and Annie to work full-time.

Without reliable income, the household uses cash transfers from Mercy Corps’ Ven Esperanza program partially to invest in a refrigerator for their kitchen and for basic needs like wood for cooking. The cash transfers from Mercy Corps will run out in two months, and the family is planning to use them to finish paying off the refrigerator. As for the free program providing Jimmarys’s medication, they are unsure how long it will last.

The household’s livelihood strategy faces a more certain and immediate challenge. Higo has decided to search for work in the United States. With luck, perhaps someday he might be able to send them remittances, but until then, the family continues living day-to-day. Higo’s contribution to their collective income is necessary to stay afloat, so the other adults are apprehensive about his plan.

Frankie and Francis acknowledge that they have no idea how they survive on the income they have. Their expenses largely exceed their income. They buy food on credit from food vendors regularly, up to $24 USD per month, but they still have to skip meals sometimes. They do not have any clothes but the ones they brought from Venezuela. On top of everything, Frankie and Francis are sending $49 USD every month to their parents and other family members still in Venezuela. They have come to rely on loans from loan sharks, with exorbitant interest of $5 USD per day. Coping as they are with daily scarcity and the predatory interest rates of loan sharks, saving is impossible. Looking down at the long list of expenses that she and her husband Frankie face, Francis tells me, “The phrase ‘Where one eats, we all eat’ is dead.”

The family continues to live in survival mode. They have no plan for the time when their debts are due and their cash assistance runs out. They have applied for PPT, a resident status which may make them eligible for more formal work, free education, and national healthcare that would include free access to Jimmarys’s medication, among other services. They haven’t thought much about what these benefits would mean for them. Perhaps their experiences of xenophobia and work discrimination by officials in the past make them skeptical of more formal job opportunities or improved healthcare access. The important thing is that for now, Jimmarys’s medication is available, and they are still able to pay for her to attend school.