One Venezuelan woman’s steady restaurant income gives her partner the freedom to weigh options and turn down risky jobs.

Nesly and Ana met two years ago through a mutual friend at Parque Boston, in the center of Medellín, Colombia. Both immigrants from Venezuela, they found that they had a lot in common, and hit things off right away. Today, they live together with their French Bulldog, Lola. Individually, they each overcame great hardship upon first arriving to Colombia, and by joining forces, they’ve been able to achieve just enough stability to allow Nelsy to turn down risky jobs in search of a better long-term fit. Even so, they continue to live month-to-month.

Nelsy’s Journey

Nelsy grew up near Caracas, Venezuela. At age 14, following neglect from her only remaining living family member, she was emancipated and began living alone. Just as Venezuela was in economic free-fall in 2018, Nelsy lost her supermarket job. She had to abandon her university studies because she could no longer afford transportation to get to school. Some days, she couldn’t even afford food. Her then-girlfriend, Beatriz, left Venezuela a month before, and Nelsy decided to follow her to Cartagena, Colombia. She arrived in November 2018.

During their first six months in Cartagena, Nelsy and Beatriz focused simply on surviving. They cleaned windshields at traffic lights, and people would pay with whatever small change they had on hand – often less than $0.25 USD. They lived in a boarding house that charged about $4.50 USD per night. Lodging like this is common for recently arrived migrants in Colombia. Instead of paying an entire month’s rent up front, boarding houses provide the flexibility of paying a small daily amount, but overall, the arrangements end up being more expensive. Nelsy explained, “Sometimes we had to choose if we were going to eat or if we were going to pay for the room. And sometimes, it was better to eat and try resolving the room issue later. There came a time when we simply couldn’t make it anymore, and we decided to leave.”

Having made up their mind to try their luck in another city, Nelsy and Beatriz hitch-hiked their way to Medellín. Again, they started out washing windshields at traffic lights. The work was always subject to the weather: rain meant no work. After some time in Medellín, Nelsy and Beatriz decided to break things off and go their separate ways.

Ana’s Journey

Ana’s journey to Colombia began not long after Nelsy’s. In January 2019, she left her hometown of Ciudad Ojeda, Venezuela. Her brother had migrated to Colombia years before, and he helped pay for Ana’s journey to Medellín. Ana landed at her brother’s place and stayed there for the first two months, helping him and his wife care for their young son.

Eventually, Ana moved out on her own, bouncing between living situations. She moved to Bello, a very poor neighborhood far up in the hills. Lying on the outskirts of Medellín, Bello is neglected by the municipality – which becomes clear when entering the neighborhood. There, the road shifts abruptly from pavement to dirt. In Bello, Ana ran into problems with a paga diario, or loan shark. She eventually paid off her debt, but not without violent threats. The loan shark held onto her passport as collateral, which she never got back, even when she paid off the loan. To this day, Ana fears returning there.

For her first job in Medellín, Ana sold sandwiches. She typically made about $7–16 USD per day in sales, from which she had to pay $4.50 USD towards her daily rent. Whatever was left over went towards food. The work was hard on her body — she roamed the length and breadth of the city to sell her sandwiches. “I know Medellín even better than I know my hometown,” she explained. Reflecting on those first months, she said, “I spent literally all day working, my feet were throbbing. Back in Venezuela, they tell you, ‘in Colombia, you arrive and you’ll have work right away,’ and that’s a lie. I had it really hard that first year. Once, I had to sleep on the street.”

Nelsy and Ana: Seeking Stability Together

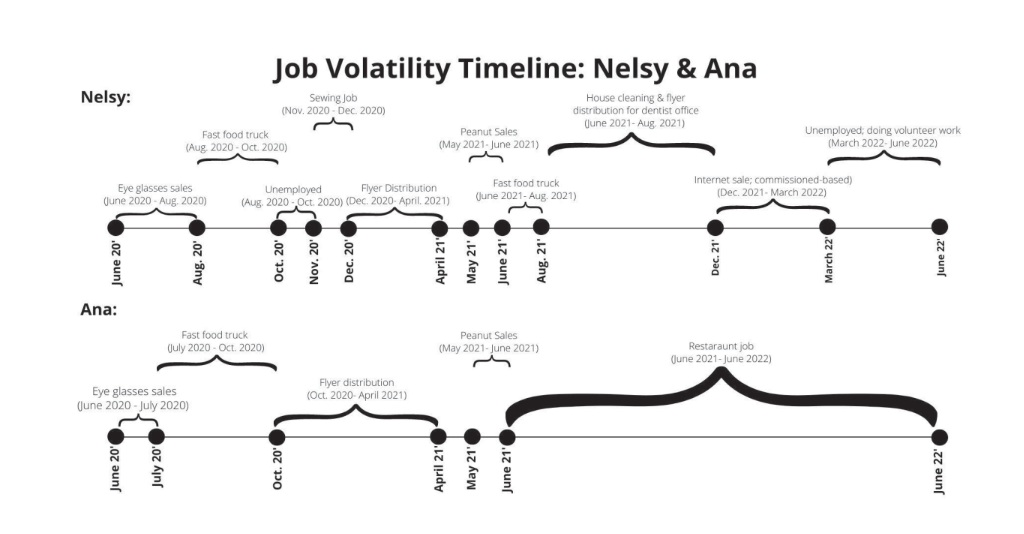

After they met in summer 2020, Nelsy and Ana worked together in a succession of brief stints. From selling eyeglasses door-to-door, to working at fast food trucks, to passing out promotional flyers, to sewing, to selling peanuts, nothing seemed to last for more than a few months. In spring 2021, for example, nation-wide protests forced Ana and Nelsy’s work to close down their promotional flyer business.

Finally, in June of 2021, Ana landed a restaurant job that has brought an important degree of stability into their joint lives. She does everything – plating food, busing, and serving tables – and has been working there for over a year now. Ana’s discipline from military school in Venezuela has helped her work hard and learn quickly on-the-job. She makes $212 USD per month at the restaurant, working 9-hour workdays, six days a week. She is paid in weekly installments of $53 USD. This rate is under the official minimum wage in Colombia, and she doesn’t receive any benefits, which she credits to being hired informally as a migrant worker.

She notes, though, that her boss helped her at a critical moment last year. Her father fell ill in September 2021, and tragically passed away not long after. To help her family, Ana took out a no-interest loan of $49 USD from her boss. She paid it back in small increments over several weeks, by taking a $7 USD cut out of her weekly paycheck.

As for Nelsy, she’s continued to jump between short-term jobs over the past year. She did house cleaning and distributed flyers for a dental clinic, sold fried plantains at a local fast-food truck (until it closed), and then did commission-based internet sales. The problem with the last job was that if she didn’t make a minimum number of sales, she didn’t get paid at all.

For now, Nelsy is unemployed. She’s received job offers, but they’ve been at wages much lower than Ana’s, already below the minimum wage. Further, businesses won’t cover any kind of insurance, even though many involve working in a kitchen or with industrial fryers, threatening a high risk of injury. Nelsy explained, “The last interview I had was with a fast-food stand, but the job would have required me to do all the different functions at once... and if an accident happened, they weren’t going to cover anything... I turned down the offer. In an area as delicate as the kitchen, where there are so many risks of accidents, the fact that they don’t want to recognize those risks is very difficult. It’s better to get sick in your own home than on the job, because in the end, you end up bearing the cost.”

Nelsy continues to weigh her options. As a 25-year-old without kids or elderly family members to care for, and given the stability of Ana’s restaurant income, Nelsy is able to wait for the right fit. In theory, landing a job in the formal labor market should be possible because she received her PPT migratory status earlier this year. But, in practice, Nelsy continues to encounter informal barriers. She applied to several call centers, and in the interviews, even though she should have been able to apply with just her PPT identification card, they still requested her passport. She doesn’t have one. She explained in frustration, “Even though PPT has been in place for an entire year now, many employers still refuse to recognize it.”

While Nelsy searches for jobs, she’s been volunteering as a coordinator for an LGBTQI+ community group through Caribe Afirmativo and Mercy Corps. This socially oriented work comes naturally to Nelsy and is a huge part of her life. In fact, it’s something she’s been involved in throughout her time in Colombia. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, she volunteered with an organization that collected leftover produce from markets and donated them to migrants and other needy families. Nelsy wants to continue this kind of work in the future — hopefully through a paid position. She noted, “Social work has motivated me for a long time now, especially now that I have the opportunity to practice it.”

As Nelsy and Ana continue living off one income, they’re just getting by. Ana sends the occasional remittance to her family when needed, but Nelsy isn’t in a position to do so; she doesn’t want to burden Ana at the moment. They both acknowledge that they’d like to save up, and each month they intend to, “but something always happens,” making saving impossible. For now, Nelsy and Ana continue to support one another as they look towards the future.