A South Sudanese man uses his time in the camp to learn skills he can take home with him.

Abdo, a family man from South Sudan, uses his experience in his town’s Village Savings and Loan Association to find employment in the Bidi Bidi Refugee Camp and help his fellow refugees fight for financial security.

“It was chaos,” Abdo said, reflecting on how the outbreak of war in South Sudan uprooted his entire life. “When fleeing, we left everything behind.”

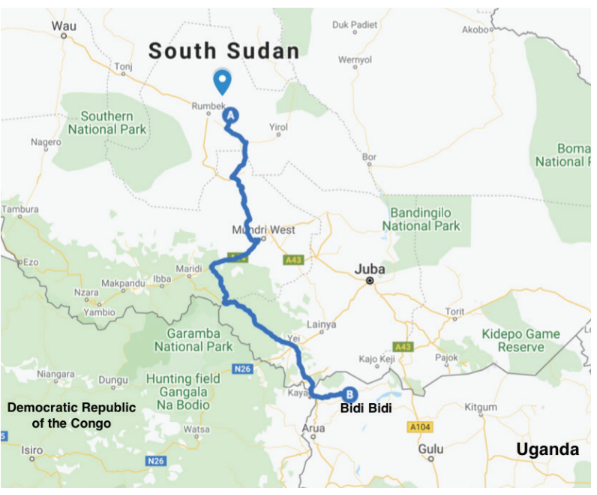

Abdo, his wife, children, and nephews arrived safely in Bidi Bidi in September 2016, but they would wait almost two years before Abdo’s brother and mother would be able to join them in the camp. His brother and mother had difficulty getting to Uganda; many roads were closed and many towns had emptied. Furthermore, they had no way to communicate with the rest of their family, and Abdo was often sick with worry about their whereabouts. On the day the family was reunited, “We celebrated in our hearts,” Abdo remembered.

Back in South Sudan, Abdo worked supporting Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLA) under a community-based organization. VSLA’s are savings and loans clubs where members purchase shares and borrow from group funds as they accumulate. Abdo trained association members on the functions of a VSLA and promoted its utility. His VSLA purchased a grinding mill and began to turn a profit, delivering yearly payouts to each of its members. With his cut, Abdo bought a motorbike. Before the war started, Abdo had about SSP 300,000 (about $85 in mid-2016) in savings through the group, about SSP 50,000 more than his motorcycle cost. He now considers that money lost forever, as the group dispersed suddenly and frantically when families began to flee.

Abdo had also worked as a county tax collector, for which he earned SSP 3,500 (about $1 in mid-2016) per month. He and his wife also operated a successful kiosk, bolstered by loans from the VSLA. Most of the income from the kiosk was devoted to paying school fees.

Abdo’s experiences with VSLAs and managing his own small business helped him assume various leadership roles in the camp’s farming and savings groups. In 2017, Abdo was hired by an NGO to help implement livelihood programs in the camp communities. His role involved registering beneficiaries, mobilizing community members to participate in the available programs, sensitization, and monitoring and evaluating the farming programming. He was paid 10,000 shillings ($2.70) per day.

This NGO provides refugees with seeds, farming tools, and training, but each VSLA needs to find land to cultivate, which has been somewhat difficult. Abdo’s group leased an acre of land from a landowner in the host community for the cost of 120,000 shillings ($32.40) per year. The group planted onions, eggplants, groundnuts, and sesame. When they harvest the eggplant, they cut the fruits into pieces and dry them before storage so that the product can be sold during the dry season.

“We harvested 110 kilograms of onions, which we sold at 3,000 shillings ($0.81) per kilogram and five basins of groundnuts sold at 18,000 shillings ($4.80) per basin,” Abdo shared, noting that the members of the group also set some aside for their own consumption.

Abdo has also formed strong relationships within the local Ugandan community. “Refugees need to create personal relationships with the host members to make it easier for them to get land for farming,” he said. The owner of the land on which Abdo’s VSLA farms has since joined the group himself, as has his wife. They joined after seeing the harvest from the farm in the first season. Abdo hopes this will lead to reduced rent for the coming year and further cooperation.

Abdo recently joined another farming group that cultivates mushrooms and has already begun selling one kilogram of mushrooms for 10,000 shillings ($2.70). Abdo said that while it’s great that mushrooms can be grown throughout the year, the process is involved and temperamental. The mushrooms, he explains, are sensitive to light, cigarette smoke, lotions, and other irritants. “It is like taking care of a very small baby,” he quipped.

The farming group had benefited from Abdo’s exposure to mushroom harvesting through his NGO employer. “I appreciate that [they] gave us seeds as startup capital, especially with the mushroom project,” he explained. “It is an all-season crop we can always sell or consume ourselves. It is also knowledge that we can use elsewhere when we decide to leave the camp. When I go back to South Sudan, I will implement this on my own farm.”

Abdo also joined another savings group in May 2019 and managed to save 500,000 shillings ($135.30) within a matter of months. He has yet to take out a formal loan from the group. “Taking loans without investing in a business is a risk,” Abdo said. However, the same group has a “social fund” from which members can borrow in times of need and repay with no interest. Abdo borrowed 20,000 ($5.40) to help his brother travel to theological college. The group of thirty democratically decides what loan requests from the “social fund” will be granted.

In South Sudan, Abdo had no access to banking institutions, but in the camp, he registered for Airtel Mobile Money. However, he has recently had complications using the account and suspects that someone has tried to use the account fraudulently and that the SIM card has been blocked as a result. Abdo’s monthly income is delivered via mobile money, so he had no choice but to navigate all the red tape involved in unblocking his account. He had to travel to Arua (for a cost of 36,000 shillings or $9.70). He decided, after this debacle, to switch to MTN Uganda for his mobile banking needs.

Still, mobile money with any company is not perfect. When people keep withdrawing and not depositing, it becomes difficult for the agents to operate. They lack the cash to fund the withdrawals. “Sometimes, the agent tells you they are only accepting deposits,” he said.

Abdo’s life in the camp is a patchwork of different incomes and activities, and it has not always been easy. There are times when his family goes for almost two months without receiving a food ration. If the food runs out before the next installment, the family must buy from the market. “I advise my wife to make sure that we do not waste any food,” Abdo said. “She should prepare the amount that is just enough to avoid wastage.”

Getting firewood is also a problem. “The host community doesn’t want us cutting trees on their land. We buy from them at 3,000 shillings ($0.81) per bundle, which lasts two to three days,” he said. Sometimes, the household is forced to sell their food in order to buy firewood. Like many other refugees, Abdo and his family have also run into medical emergencies for which the hospital is unable to provide medication. Abdo believes that camp-based organizations should prioritize health issues because “people can lose their lives on illnesses that can be treated.”

“Life was not easy when we came, but now, I can say, it has fairly improved,” he said. “But still, if I hear that the war is over, I will pack immediately and go back.”