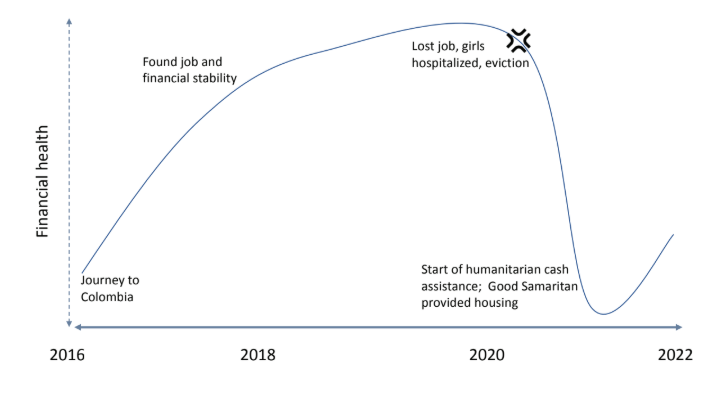

Lisbeth had successfully beat the odds to establish financial stability for her family until a combination of compounding financial shocks eroded her gains.

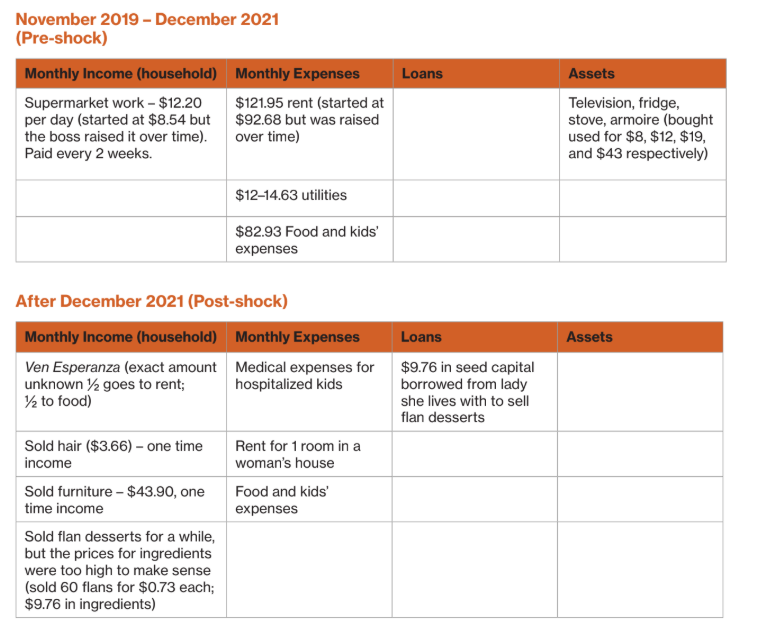

As a young, single mother of two sweet girls, Lisbeth worked tirelessly to achieve financial stability. Arriving in Colombia five years ago, she has since found a steady job that accommodated her childcare responsibilities, and she had been able to move her family into a larger apartment while effectively saving through the purchase of physical assets like furniture.

Everything changed seemingly overnight when she was hit by several combined financial shocks—the loss of her job, emergency medical expenses for the girls, and eventually eviction. When she lost the apartment because she couldn’t pay rent, she quickly had to sell off everything she owned in order to move into a spare room of another person’s house. Still, her tenacity, grit, and self-sufficiency continue to serve her well as she claws her way back from rock bottom.

Long ago twenty-eight-year-old Lisbeth accepted the fact that nothing in life would come to her served on a platter: if she wanted something, she would have to work hard for it. Like many other Venezuelans, she came to Colombia in 2016 when the Venezuelan economic situation became untenable, leaving her young daughter behind with family. And like many other Venezuelans, she had a harrowing journey through an informal smuggling route. Gangs robbed her bus and threatened women passengers with sexual violence. She lost everything she owned besides the clothes on her back and her precious documents, which she had prudently tucked under her clothes for safekeeping.

When Lisbeth first arrived in Colombia, an acquaintance living in Marinilla let her stay in a spare room for a month for free. Compared with the Venezuelan economy at the time, she was astonished at how easily she found decent jobs. She worked at a grill house clearing tables and cleaning, earning $170 USD per month. Soon Lisbeth was doing well enough to call her mother and ask her to bring her daughter to Colombia. Though she never complained, she began to realize how much the loneliness of making it on her own in a foreign country was catching up to her. In 2019, when she finally had the chance, she moved to Medellín to be closer to extended family members. A cousin hosted Lisbeth and her daughter for their first two weeks in Medellín, also helping Lisbeth find a job and a small apartment of her own.

After working a few odd jobs, Lisbeth was overjoyed to find a steady job that suited her financial, emotional, and childcare priorities. A Colombian woman she knew spoke highly of her to Oscar, the owner of a small neighborhood supermarket, and though it was a family-owned business, he gave her a trial period to prove herself. She did whatever was needed without complaint—cleaning, assisting customers, stacking boxes. The hours from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. weren’t easy, but she liked the job because Oscar was kind and generous: he provided her with two meals a day. They got along so well that he soon gave her the nickname La Monita or Little Monkey.

When Lisbeth started work in 2019, Oscar paid her $8.50 USD per day ($200 USD monthly). He periodically gave La Monita raises, so by 2021 she was making $12 USD per day ($284 USD monthly). Lisbeth knew how easy it was to spend money when she had it—it seemed to burn a hole in her pocket—and how hard it sometimes was to make it to the end of the month when she had to pay $93 USD in rent. After earning his trust, Lisbeth requested that Oscar switch from paying her daily to paying her bi-weekly. She’d learned this financial tip from a friend and found that it was much easier to make rent when she was paid bi-weekly; it was a system that forced her to save up without the temptation of making daily expenses that in some cases were unnecessary and depleted her funds. Her boss was open to the arrangement as long as she kept track of her hours. Even though she’d only completed a handful of years of primary school in Venezuela, she fastidiously wrote down her daily hours in a logbook, never erring in her arithmetic.

Lisbeth recalls pinching herself from time to time during this period. Things were going so well for her small family. She’d given birth to a second beautiful daughter and was able to support the family on her own, exactly how she liked things. She managed to enroll her older daughter in daycare. After a year working at the supermarket, she’d upgraded her family to a slightly bigger apartment with two rooms, though it was made from informal materials and not entirely completed. Above all, she was glad to have never taken on debt of any form. She feared the loan sharks in the neighborhood famous for taking advantage of families facing emergencies.

As soon as the Colombian government announced the new policy for Venezuelan migrants, she applied for her Permiso por Protección Temporal (PPT), a migratory status that would give her access to formal jobs and social services like healthcare. Only later did she discover that she’d been punished for her diligence. After months and months of waiting, she took a day off work and went to the migration authority’s office. She learned that her PPT application was stuck in a nightmarish bureaucratic limbo due to an error that had derailed the applications of many people who, like her, applied in the first month of the policy. In fact, there were so many sorry souls trapped in this process that they earned the nickname of “Septembristas” for the month in which they had all applied for the PPT.

Nearly three years later, she is still waiting for her PPT approval. Though she felt the Colombian banking system was stable than the Venezuelan system, she still didn’t trust putting her money into a formal Colombian bank account. Because she didn’t have a formal bank account, she had to save in creative ways. She did this by periodically purchasing furniture and appliances as a way of accumulating physical assets that could be later resold. Over time, she bought a television, fridge, stove, and armoire.

Though it had taken Lisbeth years to build up her family’s financial health, it evaporated seemingly overnight. In December 2021, right before the holidays, Oscar’s wife fired her saying she only wanted to have family members working in the store. Lisbeth’s two daughters both got very sick at the same time and were hospitalized. Because she had not yet received her PPT, Lisbeth had to pay $156 USD out of pocket for their treatments. Instead of showing sympathy, the landlord raised the rent even higher that month to $122 USD plus $15 USD in utilities. In February 2022, the landlord kicked Lisbeth and her two daughters out with only a few days’ notice.

Lisbeth scrambled to secure a roof over their heads. They moved in with a kind stranger who had a spare room, but little space for extra furniture. Lisbeth was forced to sell all her furniture and appliances at fire sale prices, losing nearly half of her ‘savings’ value. In a moment very near rock bottom when she needed to pay her kids’ medical expenses, she cut and sold her hair for $3.40 USD. This felt like the last option she had besides prostitution, which she adamantly refused to consider.

Lisbeth has still been able to nearly avoid taking on debt entirely. The only exception is that she asked the woman she currently lives with to lend her $9 USD as start-up capital so she could sell flan desserts (“postre quesilla”). It was not a great business, but it gave her a little cash. She stopped after a few months when the inflation on food prices spiraled too high and she could no longer turn a profit. She remains grateful to her kind neighbors who periodically help her with food, diapers, and household costs.

Still, Lisbeth says she doesn’t think many others could “aguantar la situación” if they were in her shoes. After months searching and sending out her CV, she remains unemployed and awaiting her PPT. She bitterly recalls the many times potential employers have tried to take advantage of her. “I’m fed up with being paid below minimum wage, below the salaries they pay others.”

The freefall of her financial health was slowed when Lisbeth was referred to Mercy Corps through a health clinic and began receiving monthly emergency cash assistance. Half of the transfer goes to paying rent and the other half goes to food and expenses for the kids. Nothing remains left over at the end of the month to start saving up. Always one to speak her mind, she expressed frustration that she couldn’t receive the aid as cash payments or food. She is currently receiving a lot of help from neighbors and the woman letting her stay in her apartment, but now that she is getting cash assistance, she must contribute part of the payments to rent.

Lisbeth would really like to start up a small food cart business selling empanadas, something she learned back in Venezuela. She’s priced out each type of empanada she would sell, the different costs, and the profits she’d expect. She estimates that she would need about $159 USD in seed capital. She would be able to leave her kids with her cousin during the day and then maybe she could start to slowly rebuild the financial stability and independence she cares so much about and had not so long ago achieved.