Pursuing an education in mechanical engineering while working as an entrepreneur and broker, a twenty-nine-year-old works to create opportunity.

Simon, a young man from South Sudan, struggles to obtain his mechanical engineering certification while also making a living and supporting several family members. His business endeavors have had to take the back burner to his studies in recent months, and money is tight. Simon looks forward to the day when he has the necessary qualifications to open his own mechanic’s garage and be his own boss.

“I am the one who provides for the family,” Simon, age 29, began. “I pay rent and buy food. I also pay my own school fees.” Most of Simon’s income is spent on his school fees, a cost of 350,000 shillings ($94.70) per term. Simon’s diploma course in mechanical engineering is an important step in his career journey, a journey complicated by both displacement and financial hardship.

In 2015, Simon and his sister were students in Juba when they learned their father had been killed in a crossfire between the rebel militia and government soldiers. They agreed it was time to leave South Sudan. However, their migration to Uganda was more economically motivated than it was by their lack of safety.

To journey to Kampala, Simon withdrew SSP 45,000 (about $1000 at the time) from his savings account at Equity Bank. In Juba, he had worked as a taxi driver and in construction and managed to save about SSP 3,000 ($66 at the time) per month. He hoped that Kampala would not only be safer but also prove ripe with opportunity.

“When I went to register as a refugee at the Old Kampala Police Station, I was told that they were no longer taking South Sudanese refugees,” said Simon. “They said that we are very rude.” As a result, Simon and his sister were unable to secure any documents indicating their refugee status.

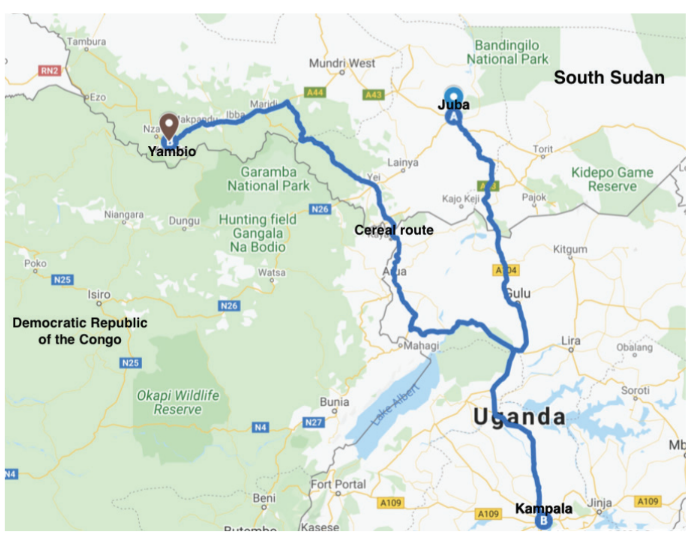

But, they still hoped to stay. “I asked my friends what they did in Kampala to survive,” Simon said. “They told me about the business of sending goods back home to sell and get your money back. Most of them were dealing with clothes and shoes. I decided to deal with cereals since there was a demand in Yambio.” Simon has other siblings living in Yambio and, with their help, has been able to coordinate the delivery and sale of cereals. His siblings receive the goods, sell them on his behalf, and then send the money to him for restocking. Simon began this business with $200 from his savings.

Simon purchases the cereals in Kampala for a cost of UGX 40,000 ($10.80) per bin. He then loads them onto trucks that travel through the Congo and onward to South Sudan. Sometimes it takes up to a month for the goods to be delivered, especially during the rainy season. His relatives receive the load, sell the goods, and then return the proceeds to Simon via MAF airline parcel delivery or a family friend traveling to Kampala. Simon’s relatives don’t take a cut of the profit. “They know that we are struggling here in Uganda,” he explained.

Even though he still has an account at Equity Bank, Simon says he has no use for its services, preferring the convenience and flexibility of mobile money instead. A friend with legal documents purchased a phone line for Simon and registered the number with Airtel. Simon said mobile money has made it easier to pay his school fees.

Simon’s cereal business has recently taken the back burner to his studies. “My business has gone down because I am busy with schoolwork,” he said. “You must hustle,” Simon continued, “I [do] any work that would give me money. Like working in construction sites.” But Simon now has his sights set higher, dreaming of more financial security and autonomy in his work life.

“I decided to do mechanical engineering because I will be self-employed. I will be the one to decide my salary and what to pay my workers,” he reflected.

During the weekdays, Simon is in school, but he works as a broker for other South Sudanese on some weekends. People send him money to purchase goods on their behalf in Kampala and then coordinate the goods’ safe delivery to South Sudan. There is no standard amount that Simon charges for his services as a broker. “It depends on the person’s generosity,” he said. His income ranges from 10,000–30,000 shillings ($2.70–$8.10), depending on the customer. It’s not much, but Simon says he needs every dollar he can earn to help cover the cost of his education.

There are more school-related fees for non-citizen students like Simon. When enrolling for the mechanical engineering course, Simon did so as a South Sudanese and not as a refugee because he lacked official refugee status. As a non-citizen, Simon will pay a 150,000 shilling ($40.60) examination fee in addition to his regular school fees while citizens will pay only 100,000 shillings ($27.00) in examination fees.

Money is so tight that sometimes Simon cannot pay their rent and is grateful their landlord is very understanding about delays.

One of Simon’s instructors recently suggested that Simon take an internship as a mechanic in a garage in Kibuye. While not paid, the internship would offer a pathway toward employment for interns who demonstrate competence. Simon is considering this opportunity but has also toyed with the prospect of returning to Juba. “Whether or not I return depends on whether I will get a well-paying job here in Uganda or not,” he said.

Simon aspires to open his own garage in Yambio someday. He plans to save up some money and then use the land he has in Yambio as collateral to get a bank loan. This is an option that, without documentation, isn’t available to him in Uganda. He joined a South Sudanese refugee organization that advocates for the official registration of people like Simon and his sister. He also hopes his sister will be able to go back to school one day and endeavors to save for her education as well. But, in the meantime, money is tight.